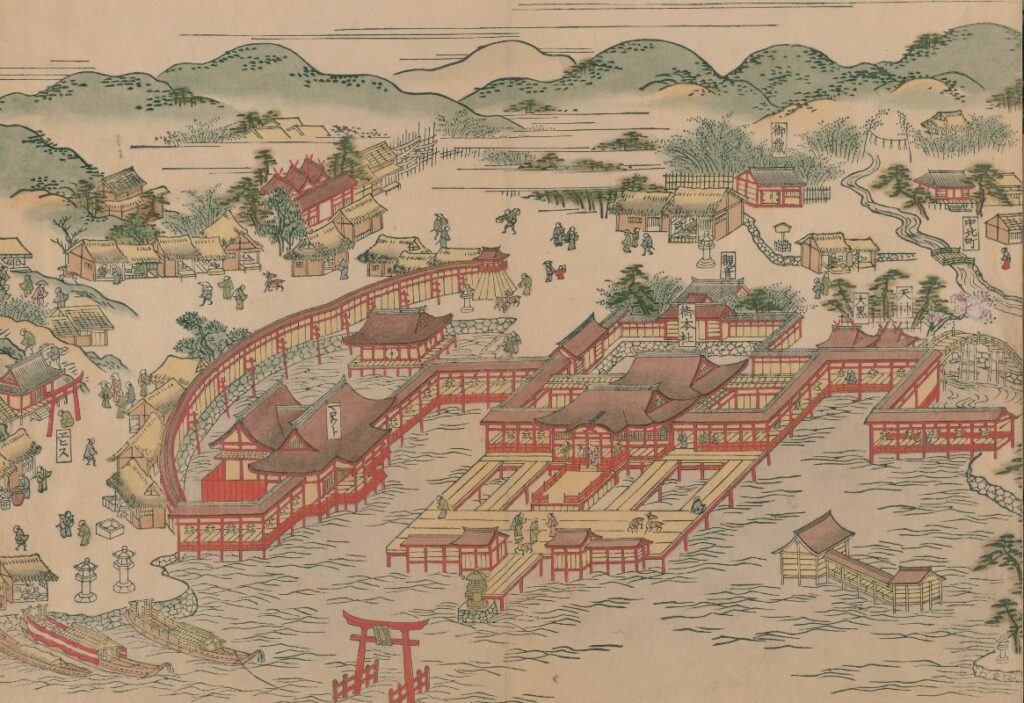

Miyajima—a sacred island floating in the Seto Inland Sea—holds a special place in Itsukushima Shrine history. Located in what was once distant Aki Province (today’s Hiroshima Prefecture), far from the imperial capital of Kyoto, this divine island became one of the most revered pilgrimage destinations for Japan’s Heian period aristocracy. Understanding this rich Itsukushima Shrine history reveals why Miyajima remains such a culturally significant destination for travelers today.

The relationship between Heian nobles and Miyajima transcended a simple visit to a provincial shrine—it represented the intersection of faith, politics, and culture. Powerful regent families like the Fujiwara clan, retired emperors during the Insei period, and the influential Heike (Taira) clan all competed to make pilgrimages and present lavish offerings at Itsukushima Shrine. This article explores the fascinating history of their devotion—why the nobility of Kyoto revered this island sanctuary—and how that thousand-year-old legacy continues to shape Miyajima’s appeal as a destination for cultural tourism and heritage travel today.

The Historical Development of Heian Aristocrats and Miyajima Worship

Early Heian Period: Shinto-Buddhist Syncretism and Miyajima’s Rising Status

In the early Heian period (794-1185), Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima gradually captured the attention of aristocrats in the imperial capital, driven by the widespread embrace of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism—the blending of Japan’s native Shinto beliefs with imported Buddhist practices. The principal deity enshrined at Itsukushima Shrine, Princess Ichikishima-hime-no-Mikoto, became identified with Benzaiten, the Buddhist goddess of music, eloquence, arts, and wealth.

This association proved particularly powerful among the Heian nobility, who prized cultural refinement and eloquence as essential qualities. Benzaiten’s promise of protection over these domains made her especially popular at court. Members of the regent houses—particularly the powerful Fujiwara clan, who effectively controlled the imperial government—actively sought her divine protection to maintain their political authority and ensure the prosperity of their lineages.

Miyajima’s designation as the “First Shrine of Aki Province” (Aki no Kuni Ichinomiya) reflected this rising fervor. The Engishiki, a comprehensive collection of regulations compiled in 905, officially records Itsukushima Shrine as a “Myojin Taisha” (Great Shrine of the Illuminated Deity)—a designation that signaled special imperial recognition and elevated status. This official acknowledgment from the imperial court confirmed Miyajima’s importance and cemented its reputation among Kyoto’s elite circles.

Regent Period: The Fujiwara Clan’s Devotion

During the 10th and 11th centuries, when regent politics reached their zenith, the Fujiwara clan deepened their devotion to Miyajima considerably. As regents (sesshō) and chief advisors (kanpaku) who effectively ruled Japan from behind the throne, the Fujiwara prioritized political stability and the continued flourishing of their family line above all else. They turned to Miyajima’s deity—understood through the lens of syncretism as Benzaiten—for divine support in these worldly pursuits.

High-ranking Fujiwara aristocrats frequently dispatched proxy worshippers to Miyajima on their behalf, accompanied by lavish dedications that demonstrated both piety and wealth. The journey from Kyoto to Miyajima was arduous and time-consuming—often taking ten days to two weeks one way—making it impractical for the most powerful nobles to travel personally. Instead, they entrusted the sacred journey to reliable retainers who would perform the rituals in their names.

The offerings presented at Itsukushima Shrine during this era ranged from meticulously transcribed sutra scrolls and elaborate ritual implements to finely crafted military equipment, ornate horse tack, and exquisite silk textiles. Each item reflected the refined taste and sophisticated aesthetic sensibility that defined Heian court culture, serving simultaneously as religious offerings and demonstrations of the donors’ status and cultural refinement.

The Insei Period: Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Reverence for Miyajima

With the advent of the Insei period in the 12th century—when retired emperors wielded power from behind the scenes—faith in Miyajima flourished to new heights. Emperor Go-Shirakawa stands out as particularly devoted to the island sanctuary. Even before ascending the throne in 1156 (Hogen 1), he demonstrated keen interest in Itsukushima Shrine and its divine protections.

One significant factor in the Emperor’s esteem for Miyajima was the influence of Taira no Kiyomori, the most powerful military leader of his time. As Governor of Aki Province, Kiyomori actively developed and enhanced Miyajima, then conveyed its splendor and spiritual significance to the imperial court. Historians believe that Emperor Go-Shirakawa, working through Kiyomori’s influence, made substantial offerings to elevate the shrine’s authority—and by extension, to support and legitimize the Taira clan’s growing political dominance.

Interestingly, while Go-Shirakawa was famously devoted to the Kumano faith (making numerous pilgrimages to the sacred Kumano mountains in present-day Wakayama Prefecture), he regarded Miyajima as the “Kumano of the Sea”—a maritime counterpart to those mountain sanctuaries. As a vital node for sea travel through the Seto Inland Sea, Miyajima became an ideal place to pray for the safety of maritime routes leading to Japan’s western provinces. This devotion skillfully blended genuine religious piety with strategic political calculation, reinforcing the power structure that elevated the Taira clan.

The Reality of Heian Aristocrats’ Pilgrimages to Miyajima

Pilgrimage Routes from the Capital to Miyajima

The journey from Heian-kyo (Kyoto) to Miyajima represented a significant undertaking, combining overland travel and maritime navigation across challenging waters. Pilgrims typically followed the Sanyo Road—the main western highway—traveling westward from Kyoto through numerous provinces until reaching Tomonoura in Bingo Province (present-day eastern Hiroshima Prefecture). This ancient port town, famous as a “tide-waiting harbor,” served as a crucial transfer point between land and sea routes.

From Tomonoura, travelers transferred to boats for the maritime leg of their journey across the Seto Inland Sea. The timing of this crossing was critical—travelers had to wait at Tomonoura for favorable tides and currents before setting sail westward. Even with ideal conditions, the sea journey required stops at intermediate harbors such as Murozumi in Suo Province (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture) before finally entering Itsukushima Bay across from the sacred island.

Weather conditions, seasonal winds, and tidal patterns could significantly prolong the trip, sometimes adding days or even weeks to the journey. These logistical challenges explain why high-ranking nobles rarely made the pilgrimage personally, instead appointing trusted proxies to perform the sacred rites and deliver precious offerings on their behalf. Even under the best circumstances, the one-way journey typically consumed ten days to two weeks—a substantial commitment of time and resources that underscored the importance aristocrats placed on honoring Miyajima’s deity.

Upon arrival at Miyajima, pilgrims underwent ritual purification along the shore (misogi), washing away the impurities accumulated during their long journey. Only after this cleansing would they proceed to the shrine itself to present sacred offerings (heihaku) and recite formal prayers (norito). Proxy worshippers carefully read prayers composed in their patrons’ names and formally presented the lavish dedications that had been transported across land and sea.

The offerings typically consisted of sutra scrolls—Buddhist scriptures painstakingly transcribed by skilled calligraphers—alongside precious objects such as mirrors (symbols of divine presence in Shinto tradition), swords, elaborate horse tack, and fine silk textiles. These luxurious items reflected not only religious devotion but also the refined aesthetic sensibility that characterized Heian aristocratic culture. Remarkably, many of these gifts survive today, preserved at Itsukushima Shrine and designated as National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties that visitors can view when exploring Miyajima’s cultural heritage.

The Many Dedicated Cultural Treasures

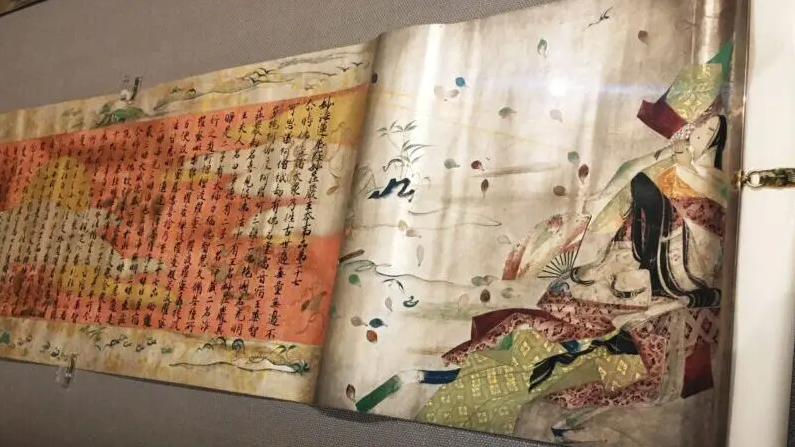

The items dedicated to Miyajima by Heian nobles represent the absolute pinnacle of courtly culture and artistic achievement during this golden age of Japanese civilization. The most famous example is undoubtedly the “Heike Nokyo” (Heike Family Sutras)—a magnificent set of Buddhist scriptures dedicated by Taira no Kiyomori in 1167. This extraordinary work involved members of the entire Taira clan in transcribing the Lotus Sutra and related texts, creating an opulent masterpiece renowned worldwide for its lavish decoration combining gold, silver, and vibrant pigments.

Another treasure of immense historical significance is the “Kunoji Sutra” (also known as the “Nationwide Sutra”)—a complete set of Buddhist scriptures transcribed in the late Heian period by multiple aristocratic families including the Fujiwara. These sutras were embellished with vivid mineral pigments and precious materials including gold and silver leaf. Now designated a National Treasure and housed in the Treasure Hall of Itsukushima Shrine, the Kunoji Sutra exemplifies the extraordinary grandeur and technical sophistication of Heian period artistry.

Among the military accoutrements dedicated to the shrine, extravagant offerings such as the “Gilded Bronze Saddle with Cloud-and-Pearl Ornaments and Openwork Carving” stand out for prioritizing ornamental beauty over practical functionality. These elaborate pieces served dual purposes—honoring the deity while simultaneously displaying the donor’s immense wealth, elevated social rank, and refined cultural sensibility to all who viewed them.

The Historical Significance of Heian Aristocrats’ Worship at Miyajima

Heian period worship at Miyajima represented far more than a purely religious phenomenon—it carried profound political, economic, and cultural significance that shaped the development of both the island and the broader region. Understanding these multiple dimensions helps modern visitors appreciate the deeper historical currents that made Miyajima such an important destination.

Politically, aristocrats in Kyoto actively strengthened their influence over distant provinces by supporting and elevating prominent local shrines. Aki Province—home to Miyajima—occupied a strategic position as a maritime hub within the Seto Inland Sea, making it absolutely critical for maintaining political and economic influence across western Japan. The Fujiwara regent house and the Taira clan both recognized Miyajima’s strategic value, using religious patronage as a tool to project power and authority into this vital region.

Economically, the continuous waves of offerings and ritual pilgrimage traffic brought substantial wealth to Miyajima and its surrounding communities. The influx of high-ranking pilgrims and their entourages stimulated the local economy through demand for boats, guides, lodging, food, and various services. Furthermore, the systematic expansion of shrine lands significantly increased Itsukushima Shrine’s economic power base within Aki Province, transforming it into a major landowner with considerable resources at its disposal.

Culturally, Kyoto’s refined court aesthetics and artistic traditions traveled westward to provincial Japan via Miyajima, creating an extraordinary cultural exchange. The donated sutras, artworks, and luxury items elevated the cultural standards of this provincial region, exposing local artisans and religious practitioners to the highest achievements of metropolitan culture. Miyajima emerged as a dynamic hub of cultural exchange that linked the sophisticated world of the imperial capital with the developing regions of western Japan, facilitating the spread of artistic techniques, religious practices, and aesthetic values.

The Enduring Value of Heian Aristocratic Faith in the Modern Era

The Heian aristocracy’s profound devotion to Miyajima continues to resonate powerfully with visitors today, making the island a must-visit destination for anyone interested in Japanese cultural heritage. Many of the National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties carefully preserved at Itsukushima Shrine were originally dedicated by these Heian period nobles over eight centuries ago. These extraordinary works remain indispensable to understanding Japanese history, religious culture, and artistic achievement, forming a major highlight of cultural tourism for visitors drawn to Miyajima’s rich historical legacy.

The Heike Nokyo stands foremost among these treasures—often regarded by art historians as the supreme masterpiece of Heian period decorated sutras and one of Japan’s most important cultural properties. Each year, researchers, art lovers, and culturally curious travelers from around the world visit Miyajima specifically to experience these treasures firsthand and encounter the refined world of Heian aristocratic faith and artistic expression. The Treasure Hall at Itsukushima Shrine provides visitors with carefully curated displays of these precious objects, offering intimate glimpses into the aesthetic sensibility and spiritual devotion of Japan’s golden age.

The traditional pilgrimage route from Kyoto to Miyajima also continues to inspire modern travelers seeking meaningful connections with Japanese history. Retracing historic paths across the Seto Inland Sea—whether by ferry or more leisurely cruise—allows contemporary visitors to experience something of the journey that once drew nobles to this sacred island. Standing before the famous floating torii gate or walking through Itsukushima Shrine’s elegant vermilion corridors, travelers can sense the same reverence and wonder that captivated emperors, regents, and warrior lords a millennium ago.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Heian nobles worship at the distant Miyajima?

Heian aristocrats revered Miyajima because Ichikishima-hime-no-Mikoto, the principal deity of Itsukushima Shrine, was identified with Benzaiten—the Buddhist goddess of music, eloquence, arts, and wealth. These domains were highly valued by the cultured Heian nobility, who sought Benzaiten’s divine protection to enhance their political influence and cultural accomplishments. Additionally, Miyajima’s strategic position as a major hub on the Seto Inland Sea made it politically important for maintaining influence over western Japan, meaning that religious devotion aligned perfectly with practical political goals.

Did the Fujiwara clan actually visit Miyajima in person?

Historical records show that few high-ranking Fujiwara regents and chief advisors traveled to Miyajima personally. Instead, most appointed trusted retainers to serve as proxies who would make the pilgrimage on their behalf. The practical reasons were straightforward—the one-way journey from Kyoto to Miyajima typically required ten days to two weeks even under favorable conditions, making frequent personal visits by the realm’s most powerful nobles impractical given their demanding political responsibilities in the capital.

What was Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s relationship with Miyajima?

Emperor Go-Shirakawa held extraordinarily deep reverence for Miyajima and made numerous substantial offerings through his ally Taira no Kiyomori. While the emperor was also famously devoted to the Kumano faith (making multiple pilgrimages to the Kumano mountain sanctuaries), he regarded Miyajima as the “Kumano of the Sea”—a maritime counterpart to those mountain shrines and a sacred site for prayers ensuring safe sea travel to Japan’s western provinces. This devotion likely served political purposes as well, helping to reinforce and legitimize the Taira-led political order that Go-Shirakawa supported.

Are any of the cultural treasures donated by Heian nobles still preserved today?

Yes, many extraordinary cultural treasures are beautifully preserved at Itsukushima Shrine today, making Miyajima an essential destination for anyone interested in Japanese cultural heritage. The most famous is the National Treasure “Heike Nokyo” sutra set dedicated by Taira no Kiyomori—widely considered one of Japan’s most important art objects. Other precious items including sutras, ceremonial mirrors, ornate swords, and elaborate horse tack also survive from the Heian period. Selected masterworks are regularly displayed at Miyajima’s Treasure Hall, where visitors can view these thousand-year-old treasures that represent the pinnacle of Heian aristocratic culture and religious devotion.

What route did pilgrims take from the capital to Miyajima?

Pilgrims traveled westward from Kyoto along the Sanyo Road (the main western highway) through multiple provinces until reaching Tomonoura in Bingo Province (present-day eastern Hiroshima Prefecture). At this famous “tide-waiting port,” travelers transferred to boats and continued their journey across the Seto Inland Sea. Pilgrims had to wait at Tomonoura for favorable tides before sailing, typically resting at intermediate harbors such as Murozumi in Suo Province before finally entering Itsukushima Bay opposite the sacred island. Even under ideal conditions, the one-way journey required ten days to two weeks—a substantial commitment that underscored how highly aristocrats valued Miyajima worship.

How did Shinto-Buddhist syncretism influence the faith at Miyajima?

Through the process of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism (the blending of Japan’s native Shinto beliefs with imported Buddhist teachings), the Shinto deity Ichikishima-hime-no-Mikoto was identified with the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten. This created a distinctive system of worship centered on a Shinto shrine while simultaneously incorporating Buddhist elements, practices, and theological concepts. This fusion proved particularly appealing to Heian period elites, who valued both traditions, and remains a fascinating hallmark of Japanese religious culture. The seamless coexistence and interweaving of Shinto and Buddhism at Miyajima exemplifies the uniquely Japanese approach to spirituality, where multiple religious traditions have long complemented rather than competed with one another.

Summary

For Heian period nobles, Miyajima represented far more than a provincial shrine situated in a distant corner of the realm—it was a crucial focal point of religious faith where politics, economics, and culture dynamically intersected. The powerful Fujiwara regent houses, Emperor Go-Shirakawa during the Insei period, and the militarily dominant Taira clan all competed earnestly to honor Itsukushima Shrine with sumptuous offerings that demonstrated both their piety and their wealth.

Many of these precious dedications—lovingly transported by proxy pilgrims after arduous journeys requiring over ten days each way across land and sea—are carefully preserved at Itsukushima Shrine today as National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties. These extraordinary objects testify to the profound depth of Heian devotion and showcase the refined aesthetic sensibility that characterized Japanese court culture during its golden age. Rooted in the fascinating tradition of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, the faith that united Princess Ichikishima-hime with the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten at Miyajima stands as a vivid and enduring symbol of Japanese religious culture’s unique character.

The political, economic, and cultural significance of Heian era worship at Miyajima continues to offer rich insights for modern visitors interested in understanding how this island became such an important pilgrimage destination. Visiting the cultural properties preserved at Itsukushima Shrine provides a meaningful, tangible connection to history—an opportunity to walk in the footsteps of emperors and nobles, to rediscover the reverence they felt standing before this sacred island, and to appreciate the enduring value of the extraordinary cultural heritage they left behind for future generations to treasure.

References & Sources

- Agency for Cultural Affairs Cultural Heritage Online: Itsukushima Shrine (World Heritage Site)

- Agency for Cultural Affairs National Designated Cultural Properties Database: Itsukushima Shrine

- Hiroshima Prefectural Board of Education Cultural Properties Division

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website: History

- Miyajima Tourism Association: World Cultural Heritage Registration

- Nara National Museum: Itsukushima Shrine National Treasures Exhibition

- Hiroshima Prefectural University Miyajima Studies Center

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, Miyajima Town History: General History Volume, Miyajima Town, 1992

- Fumihiko Gomi, Research on the Insei Period Society, Yamakawa Publishing, 1984

- Yasuo Motoki, Taira no Kiyomori and Emperor Go-Shirakawa, Kadokawa Shoten, 2012

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Itsukushima Shinto Shrine