When travelers search for Miyajima fall foliage, they’re almost always led to one magical spot: Momijidani Valley. This peaceful valley stretches across the foot of Mount Misen and is home to roughly 700 maple trees that paint the landscape in different shades throughout the year. While it’s beloved for its fiery autumn colors, Momijidani Park holds a deeper story—one of careful development that began in the Edo period, remarkable recovery from a devastating postwar disaster, and a landscape uniquely shaped by both nature and human dedication.

Momijidani is a rare place where history and nature truly harmonize—born from Edo-period passion and postwar innovation. The park unfolds along the crystal-clear Momijidani River with a rich mix of Japanese maple varieties. From the fresh greens of spring to the brilliant reds of late autumn, the scenery continues to captivate visitors traveling to Miyajima and Hiroshima. This article traces how Momijidani took shape and reveals the enduring charm behind its beauty.

Momijidani’s Historical Background and Traces of Development

Edo Period Development and the Birth of a Famous Spot

The story of Momijidani begins centuries ago in the Edo period (1603-1868), when this valley at the base of Mount Misen was already celebrated for its natural beauty. Historical records from that era describe it as “a place of clear streams and ancient trees, a secluded realm named for its many maples,” suggesting it had long been admired for its spectacular autumn foliage displays.

In the late Edo period, local visionaries undertook dedicated improvements to make the valley more accessible to visitors. Led by the founder of the historic inn Iwaso, they planted maple saplings throughout the valley, constructed bridges over the stream, and opened traditional teahouses where travelers could rest and enjoy the scenery. The graceful Momiji Bridge, built during this time, remains one of the most beloved and photographed features of Momijidani Park today.

A Scenic Spot Counted Among the Eight Views of Itsukushima

For centuries, Momijidani has been celebrated as one of the prestigious Eight Views of Itsukushima, specifically known as “Tanigahara Biroku” (Deer in the Valley). The view from the Tanigahara area on the eastern side of the valley—where Miyajima’s famous deer wander gracefully among the maple-filled landscape—captured the hearts and imaginations of poets and painters throughout Japanese history.

Throughout the Edo period, Momijidani grew in importance as a place of rest and contemplation for pilgrims and travelers visiting Miyajima and the sacred Itsukushima Shrine. In autumn, combining shrine worship with a leisurely stroll through Momijidani’s maple-covered paths became a classic itinerary, cementing the valley’s role as an essential attraction on the island.

Development in the Meiji Era and Visits by Cultural Figures

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Momijidani saw even further development as Miyajima grew as a tourist destination. Traditional inns such as Iwaso flourished and welcomed distinguished guests including royalty, statesmen, and cultural luminaries who found peace in the gentle sound of the Momijidani River and the subtle gradations of maple color shifting through the seasons.

Period photographs from this time show elegantly dressed visitors strolling along the clear stream, pausing to admire the reflections of maple branches dancing on the water’s surface. The beloved Hiroshima confection “momiji manju”—steamed cakes shaped like maple leaves—also emerged during the Meiji era, directly inspired by the maple scenery of Momijidani Park. This sweet treat remains one of Miyajima’s most iconic souvenirs and stands as delicious evidence of the valley’s deep cultural impact on the island.

Features and Natural Charms of Momijidani

A Landscape Woven by Approximately 700 Maple Trees

Today, Momijidani Park features around 700 carefully maintained maple trees creating one of western Japan’s most spectacular fall foliage displays. The breakdown includes about 560 Iroha Kaede (Japanese maple, the variety you might recognize from Japanese gardens), roughly 100 Oomomiji (large-leaved Japanese maple with particularly dramatic autumn colors), plus around 40 each of Urihada Kaede (Japanese striped maple) and Yamamomiji (Japanese mountain maple). Because each of these species peaks at slightly different times throughout the fall season, visitors can enjoy an extended autumn foliage viewing period that shifts and evolves over several weeks.

From spring through summer, maple leaves quietly store starch through photosynthesis. When autumn’s first frosts arrive, that stored starch transforms into anthocyanin—the pigment that produces those vivid reds and oranges we associate with fall. The intensity of the color depends directly on anthocyanin levels, which is why day-to-night temperature differences and abundant sunshine play such a crucial role in how brilliant the leaves become each year.

A Valley Beauty That Reveals Its Expressions Through the Seasons

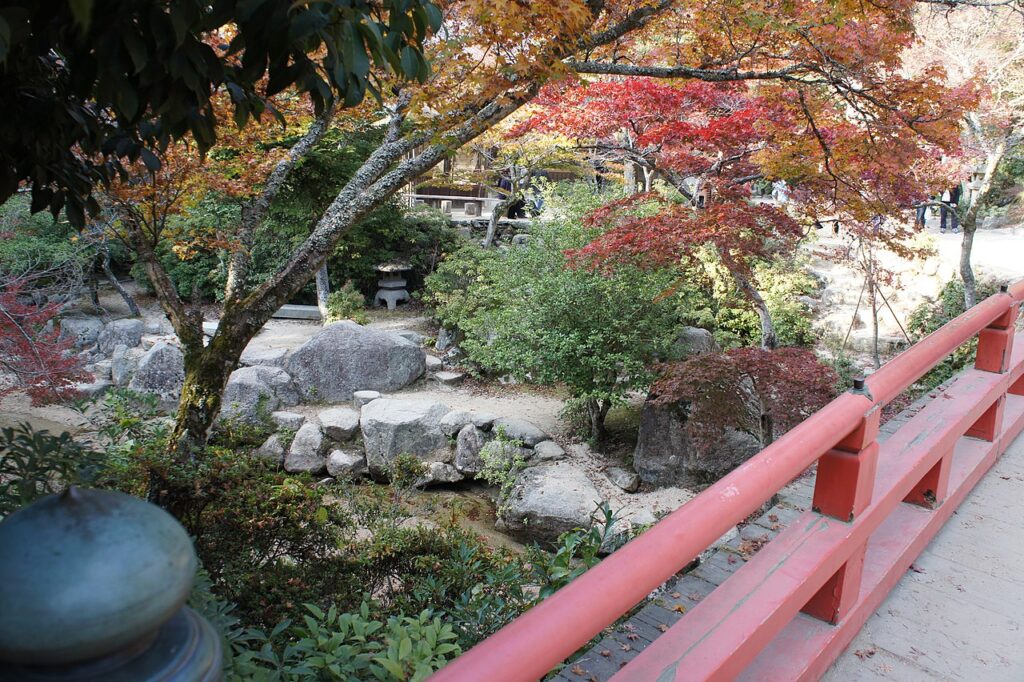

While Momijidani is most famous as a Miyajima fall foliage destination, the valley captivates visitors in every season—not just during peak autumn colors. The fresh green leaves that emerge from spring through early summer are especially refreshing and peaceful, earning the valley recognition as one of Japan’s top spots for viewing vibrant spring maple foliage. The contrast between the vermilion-lacquered Momiji Bridge and the lush green canopy creates a scene every bit as photogenic as any fall vista.

The crystal-clear Momijidani River is an essential part of the park’s serene atmosphere. The gentle sound of water threading through smooth stones brings an immediate sense of calm to travelers walking the valley paths. One of the park’s signature views, beloved by photographers visiting from around the world, is the reflection of the vermilion bridge perfectly mirrored in the glassy stream—a view best captured from the bridge itself on still mornings.

Conditions for Autumn Foliage and the Mechanism of Peak Color

For maple leaves to turn their most brilliant shades of red and orange, several environmental conditions come into play: a sharp temperature difference between day and night (which Momijidani experiences naturally), strong direct sunlight, moderate humidity, and good airflow through the valley. The color transformation typically begins when minimum temperatures dip below 8°C (about 46°F) and then accelerates rapidly when temperatures reach around 5-6°C (41-43°F).

Nestled at the foot of Mount Misen, Momijidani Park benefits from cool mountain breezes that flow naturally along the river valley, creating ideal conditions that make it one of Miyajima’s absolute best spots for autumn foliage. Peak viewing crowds gather from mid to late November each year, though in recent years the timing has sometimes shifted into early December due to warming climate patterns—something to keep in mind when planning your visit.

The Makurazaki Typhoon and the History of Recovery | The Birth of Garden Erosion Control

The Devastating Disaster of 1945

On September 17, 1945—just one month after the end of World War II—the catastrophic Makurazaki Typhoon struck Miyajima head-on. With a central pressure of 916.1 hectopascals (one of the most intense typhoons ever recorded in Japan), it unleashed devastating damage throughout the valley that would reshape Momijidani’s future.

A massive landslide high in the mountains triggered a debris flow of roughly 3,000 cubic meters that roared down through Momijidani Valley, picking up trees, rocks, and soil as it descended and growing even more destructive with every meter. Bridges were swept away, nearby inns were destroyed or buried, and even the sacred Itsukushima Shrine downstream suffered extensive damage. Historical records indicate that approximately 18,000 cubic meters of sediment—an almost unimaginable volume—flowed into the shrine’s grounds, burying pathways and structures.

Postwar Reconstruction and the Miracle of International Cooperation

More than a year after the disaster, full-scale debris removal still had not been completed due to the chaos and resource shortages of postwar Japan. In 1948 (Showa 23), the Ministry of Education finally approved restoration work, including the Momijidani area, under the official designation “Historic Sites and Places of Scenic Beauty: Itsukushima Disaster Restoration Project.”

Remarkably, the work advanced through an unprecedented cooperation among the Japanese national government, Hiroshima Prefecture, and even the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP)—the American occupation authority. Securing international collaboration for cultural restoration amid the turmoil of postwar occupation was extraordinary and underscored the global recognition of Itsukushima’s cultural and historical value as a World Heritage site.

The Innovative Technique of “Garden Erosion Control”

A special committee—the Historic Site and Place of Scenic Beauty Itsukushima Disaster Restoration Project Committee—carefully drafted a groundbreaking “Statement of Purpose for Constructing a Rock Garden Park,” ensuring the restoration work would fully respect the site’s cultural heritage while also preventing future disasters. From this vision emerged the world’s first example of what came to be known as “Garden Erosion Control” (Teien Sabo).

The guiding statement set bold and unprecedented principles: “Do not damage or split boulders or stones of any size; use them exactly as nature placed them,” “Do not cut down a single tree,” and “Conceal all artificial structures from view.” In other words, engineers and gardeners were challenged to achieve full erosion control functionality while simultaneously expressing the subtle aesthetics of a traditional Japanese garden—something that had never been attempted anywhere in the world.

Design leadership came from the Hiroshima Prefectural Civil Engineering Department, with construction carried out by skilled Hiroshima-based landscape gardeners who understood both structural engineering and aesthetic principles. Work began in 1948 and continued steadily for two years, ultimately costing roughly 80 million yen at the time (equivalent to about 130 million yen in today’s currency). The project was completed in 1950 (Showa 25), and since that time, no landslides have occurred in Momijidani Valley—a testament to both its functional success and elegant design.

Designation as an Important Cultural Property

In December 2020, the Momijidani Valley Garden Erosion Control Facility achieved a historic milestone by becoming Japan’s first postwar civil engineering structure to be designated an Important Cultural Property by the national government. The designation recognized not only its ongoing disaster-prevention function after 70 years, but also its groundbreaking technical innovation and the remarkable determination of those who worked to safeguard cultural heritage during the difficult postwar years.

The facility has been praised both for its exceptional safety record (no major incidents in over seven decades) and for creating a garden landscape that blends so seamlessly into the natural environment that most visitors never realize they’re walking through a sophisticated erosion control system. The project demonstrated that sophisticated engineering and refined aesthetic design could be achieved even amid severe postwar shortages of materials and resources—truly representing a small miracle on Miyajima.

Momijidani’s Value Passed Down to the Present Day

Today, Momijidani Park stands as one of Miyajima’s most treasured attractions, drawing visitors throughout all four seasons. In November especially, travelers from across Japan and around the world make the journey to witness the peak Miyajima fall foliage during their visits to Hiroshima and Itsukushima Shrine.

But Momijidani’s true value extends far beyond its scenic beauty. The landscape you see today is supported by centuries of dedicated stewardship: the vision of Edo-period pioneers who first developed the valley, the innovative postwar engineering that protected it from future disasters, and the ongoing conservation efforts that maintain its health. The groundbreaking “garden erosion control” approach developed here has become a model studied worldwide for how to combine effective disaster prevention with sensitive landscape preservation.

In recent years, dedicated local groups such as the NPO Sakura Momiji no Kai (Cherry Blossom and Maple Association) have actively supported conservation efforts through careful soil improvement, pruning of diseased or dead branches, and environmentally-sensitive pest control—all ensuring the valley’s beauty and ecological health will be passed intact to future generations.

With rising visitor numbers each year comes increased pressure on tree roots and soil compaction along popular pathways. Local residents, botanists, and heritage experts continue their collaborative maintenance work to protect the precious maple trees that define Momijidani. This is a living cultural landscape shaped through the long coexistence and mutual respect between people and nature. Understanding its deeper value—and helping to preserve it through mindful visiting—is part of the privilege and responsibility we all share when we walk these beautiful paths.

Frequently Asked Questions

When is the best time to see the autumn leaves in Momijidani?

The peak viewing period for Miyajima fall foliage at Momijidani is typically mid to late November, with some years extending into early December depending on weather patterns. The leaves begin their color transformation when minimum temperatures drop below 8°C (about 46°F) and the change accelerates rapidly around 5-6°C (41-43°F). Climate variations have been shifting these dates slightly later in recent years, so it’s worth checking current conditions if you’re planning a specific visit date.

What types of maple trees are in Momijidani Park?

Momijidani Park is home to approximately 700 maple trees representing several species. The most common is Iroha Kaede (Japanese maple) with about 560 trees—the classic maple variety you might recognize from Japanese gardens. You’ll also find around 100 Oomomiji (large-leaved Japanese maple), which produces particularly dramatic autumn colors, plus about 40 each of Urihada Kaede (striped maple) and Yamamomiji (mountain maple). This wonderful diversity stretches the foliage season over several weeks and creates rich variation in colors and textures throughout the valley.

When did Momijidani become known as a tourist destination?

Momijidani was already renowned as early as the Edo period (1603-1868). Contemporary historical records describe it as “a place of pure streams and ancient trees, a secluded realm named for its abundance of maples,” and it was cherished as one of the Eight Views of Itsukushima (specifically “Deer in the Valley”). The late Edo period saw dedicated development with maple plantings, bridge construction, and teahouse establishments that transformed it into a formal destination for travelers.

How severe was the damage from the Makurazaki Typhoon?

The destruction was catastrophic. On September 17, 1945 (Showa 20), just one month after the end of World War II, a massive debris flow swept through Momijidani Valley and sent approximately 18,000 cubic meters of sediment—an almost unimaginable volume—cascading into the grounds of Itsukushima Shrine downstream. The disaster destroyed bridges, buried or damaged inns and facilities throughout the valley, and left the sacred shrine grounds covered in rocks, trees, and mud. Recovery took years of dedicated effort involving national, prefectural, and even international cooperation.

What is Garden Erosion Control?

Garden Erosion Control (Teien Sabo in Japanese) is a pioneering technique developed during Momijidani’s disaster recovery that brilliantly unites the practical function of erosion control with the refined aesthetics of traditional Japanese gardens. Guided by unprecedented principles like “do not damage or split any stones,” “do not cut down any trees,” and “hide all artificial structures from view,” this approach achieves both effective disaster prevention and sensitive landscape preservation. The Momijidani facility was the world’s first example of this technique and has become a model studied internationally. In 2020, it became Japan’s first postwar civil engineering structure designated as an Important Cultural Property.

Where is Momijidani Park and how do I get there?

Momijidani Park is conveniently located about a 5-minute walk inland from Itsukushima Shrine and roughly 20 minutes on foot from Miyajima Pier where the ferry from Hiroshima arrives. The park spreads along the valley at the base of Mount Misen. If you’re planning to take the Miyajima Ropeway up the mountain, it’s a gentle 10-minute walk from the main park area to Momijidani Station where you catch the ropeway. After your stroll through the maples, consider exploring Miyajima’s famous food scene—grilled anago rice (conger eel), fresh oysters, and momiji manju are all favorite picks for travelers searching “what to eat in Miyajima.”

Can I enjoy Momijidani in spring or summer too?

Absolutely! While Momijidani is most famous for Miyajima fall foliage, the valley offers completely different but equally beautiful experiences in other seasons. From spring through summer, Momijidani is celebrated for its vibrant fresh green maple leaves and the wonderfully cool air that flows along the riverside paths—a refreshing escape from summer heat. The striking contrast between the vermilion Momijibashi Bridge and the lush green canopy creates a serene beauty that’s entirely different from autumn’s fiery colors, making Momijidani a rewarding destination worth visiting year-round.

Summary

Momijidani Park’s present form emerged through a remarkable arc of history: visionary Edo-period development, flourishing growth during the Meiji era, and an innovative recovery after the devastating 1945 Makurazaki Typhoon. The postwar “garden erosion control” system developed here became a global model for balancing effective disaster prevention with sensitive scenic preservation, ultimately earning designation as Japan’s first postwar civil engineering Important Cultural Property.

The seasonal landscapes created by roughly 700 carefully maintained maple trees embody not only natural beauty but also the deep passion and sophisticated technical skill of generations who have cared for this valley. When you visit Miyajima and walk the peaceful paths of Momijidani, take a moment to reflect on the deeper story behind those beautiful maple leaves—understanding the valley’s history and ongoing conservation will help you appreciate its charm on an entirely different level. Whether you’re seeking spectacular Miyajima fall foliage in November or the serene green canopy of summer, Momijidani offers a connection to both nature and human dedication that makes every season special.

References & Sources

- Miyajima Tourism Association: Momijidani Park

- Wikipedia: Momijidani Valley Garden Sand Control Facility

- Ganso Momiji Manju Hakata-ya: 7 Recommended Autumn Foliage Spots in Miyajima

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, Miyajima Town History: General History Volume, Miyajima Town, 1992