In the late Heian period, one visionary warrior transformed Miyajima forever, creating the breathtaking shrine that draws millions of visitors today. That man was Taira no Kiyomori, the first samurai to rise to the exalted rank of Grand Minister of State—and the architect of Miyajima shrine history as we know it.

In 1168, Taira no Kiyomori orchestrated the grand reconstruction of Itsukushima Shrine, transforming it into the magnificent “floating shrine” that seems to hover above the waves of the Seto Inland Sea. This wasn’t simply a restoration project or an act of religious devotion—it was a bold declaration of power, ambition, and cultural vision. Kiyomori’s choice to lavish resources on this remote island shrine revealed his strategic brilliance: here, military dominance, spiritual faith, control of vital sea routes, and immense wealth from international trade converged into one extraordinary monument.

The Historical Background of Taira no Kiyomori and Itsukushima Shrine

His Appointment as Governor of Aki and His First Encounter with Miyajima

Taira no Kiyomori’s profound connection with Itsukushima Shrine began in the second year of the Kyuan era (1146), when he was appointed Governor of Aki Province at just 29 years old. Aki Province encompassed the western portion of present-day Hiroshima Prefecture and served as an absolutely crucial gateway for maritime traffic flowing through the Seto Inland Sea. This seemingly routine regional appointment would fundamentally reshape both Kiyomori’s destiny and the future of the entire Taira clan.

As Governor of Aki, Kiyomori quickly recognized the strategic importance of his position. He set about consolidating control over the vital Seto Inland Sea shipping routes and, through this control, began accumulating truly staggering wealth via maritime trade. The Inland Sea functioned as Japan’s most important commercial highway, particularly as the essential corridor linking the Japanese islands with Song Dynasty China across the East China Sea. By effectively dominating these waterways, Kiyomori dramatically expanded the Taira clan’s economic foundation and political influence. The imported goods flowing from Song—copper coins that revolutionized Japan’s monetary system, exquisite ceramics, precious books and manuscripts, rare medicines, fine silks, and countless other luxury items—had a transformative impact on Japanese society and culture during this pivotal period.

According to the famous medieval epic The Tale of the Heike, a pivotal moment occurred when Kiyomori made a pilgrimage to Mount Koya, the sacred Buddhist mountain. There, a monk shared a divine prophecy with him: “If you undertake the construction of Itsukushima Shrine, you will surely attain the highest rank in the land.” This oracle, combined with Kiyomori’s growing personal faith in the island’s deity, cemented his lifelong devotion to Itsukushima and set the stage for the remarkable transformation that would follow.

First Pilgrimage in Eiryaku 3 and the Deepening of His Devotion

Kiyomori made his historic first pilgrimage to Itsukushima Shrine in August of Eiryaku 3 (1160), arriving fresh from his decisive victory in the Heiji Rebellion. In that conflict, he had defeated his rival Minamoto no Yoshitomo and firmly established Taira supremacy over the imperial court. That same momentous year, Kiyomori rose to Junior Third Rank, officially joining the ranks of the court nobility—an unprecedented achievement for someone of warrior origins. Amid all this political turbulence and personal triumph, he traveled to the sacred island to offer heartfelt thanks to the deity of Itsukushima for granting him victory and protecting the Taira clan.

This first visit marked the beginning of an increasingly intense spiritual relationship. Kiyomori forged particularly close ties with the shrine’s chief priest, Saeki Kagehiro, establishing what would become a special, almost familial bond between the Taira clan leadership and Itsukushima Shrine’s religious authorities. From that point forward, Kiyomori visited Miyajima multiple times each year, often bringing his entire family and retinue. He didn’t arrive empty-handed—he brought with him the refined performing arts and sophisticated cultural traditions of Kyoto, dedicating elaborate musical performances and elegant court entertainments during his pilgrimages. The island, once a relatively remote sacred site, gradually transformed into a showcase of aristocratic Heian culture.

The Taira Clan’s Magnificent Offering of Sutra Copies in 1164

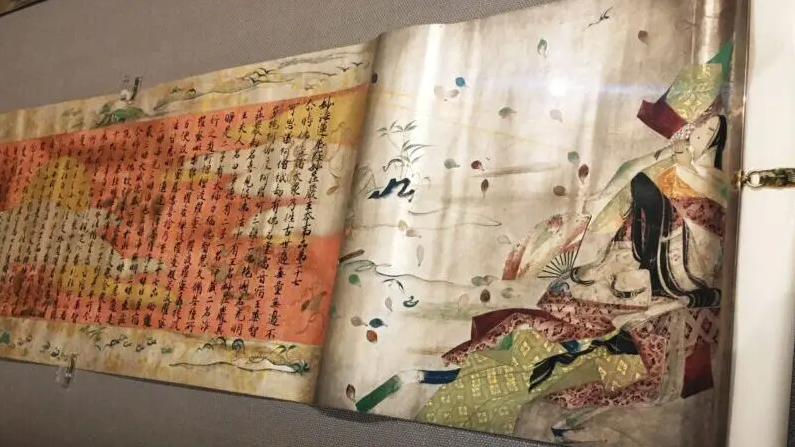

The absolute pinnacle of Kiyomori’s devotion to Itsukushima came with the Taira clan’s lavish dedication of illustrated sutra scrolls in September 1164—an offering so spectacular it remains legendary nearly 900 years later. The project began with a deeply personal prayer text penned in Kiyomori’s own hand, establishing the spiritual foundation for what followed. Then came contributions from his sons and close relatives: Taira no Shigemori, Taira no Munemori (not Yoritomo—that’s a Minamoto name), Taira no Norimori, and other family members. In total, the clan dedicated 33 volumes, including all 28 chapters of the Lotus Sutra, the Opening and Closing Sutras, the Amitabha Sutra, and the Heart Sutra—with each precious volume meticulously transcribed by a different member of the Taira family.

The decoration of these scrolls represented nothing less than the pinnacle of Heian period craftsmanship and artistic achievement. The scrolls featured scattered gold and silver leaf (kirikane technique), brilliant colored underdrawings (gansai), intricate patterns, and breathtaking attention to every detail. Every single element—the ornate covers, delicate endpapers, specially prepared paper, elaborate metal fittings, silk cords, and carved scroll rods—reflected both the immense wealth of the Taira clan and their refined aesthetic sensibility. Legend even claims that Kiyomori demonstrated his extreme devotion by mixing his own blood into the ink used for transcription, though scholars debate whether this dramatic tale is literal truth or symbolic expression of his commitment.

The chosen number—33 volumes—carries deep religious significance. It reflects the Thirty-Three Manifestations of the Eleven-Faced Kannon (Kanzeon Bosatsu), understood to be the true form of Itsukushima’s principal deity. Through this offering, Kiyomori prayed for prosperity and happiness in both this life and the next, presenting the highest possible tribute to the deities and buddhas enshrined at Itsukushima. Today, this collection is known as the Heike Nōkyō (Taira Clan Sutra Dedication) and is designated a National Treasure of Japan. Art historians worldwide acclaim it as the supreme masterpiece of Japanese decorated sutra scrolls—an unmatched fusion of religious devotion, calligraphic skill, and artistic beauty.

Characteristics and Technical Details of the Grand Shrine Reconstruction

The Ambitious Large-Scale Construction Project of 1168

Taira no Kiyomori undertook the complete reconstruction of Itsukushima Shrine in the third year of the Ni’an era (1168). At 51 years old, he had already achieved what no warrior had accomplished before: he held the highest office in the land as Junior First Rank, Grand Minister of State (Daijō-daijin). Kiyomori firmly believed that this unprecedented rise to power for someone of samurai origins had been granted through the divine protection of Itsukushima’s deity—and now he would repay that divine favor with the most magnificent shrine Japan had ever seen built over water.

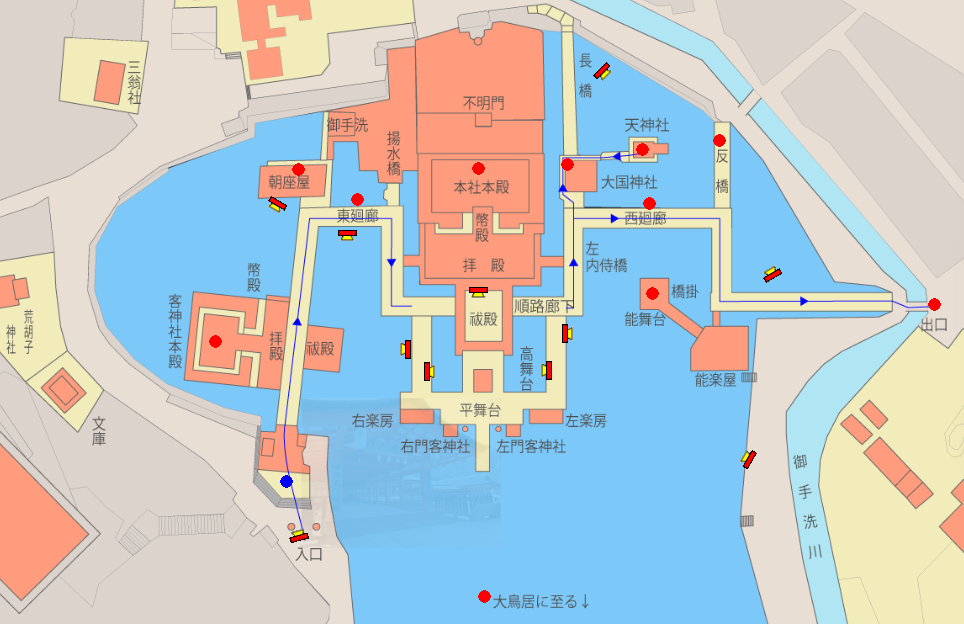

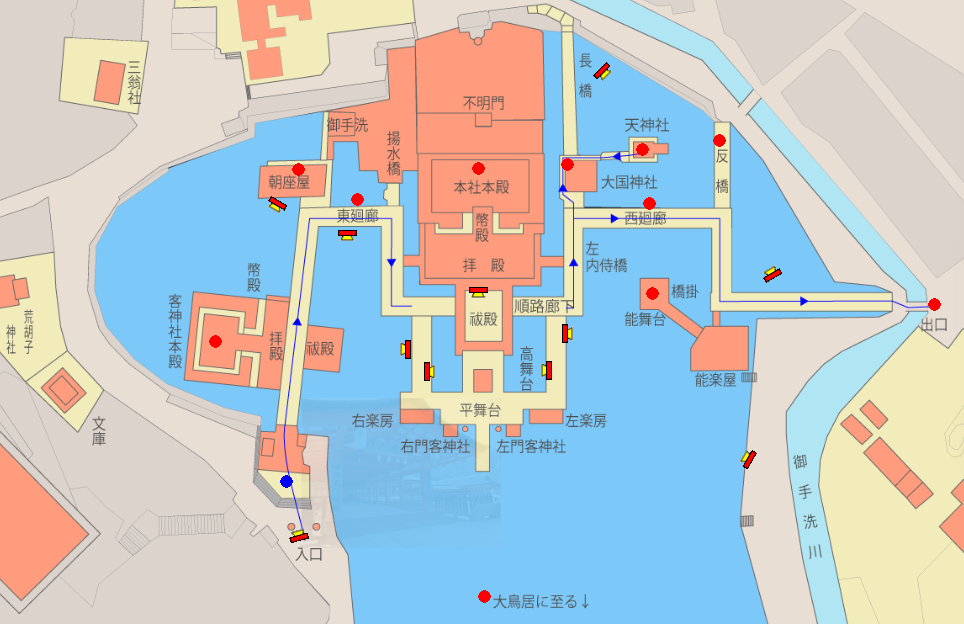

The reconstruction project was truly monumental in scope and ambition. Kiyomori transformed what had been a relatively modest waterfront shrine into the awe-inspiring maritime architectural complex that draws visitors from around the world today. The shrine precincts expanded severalfold from their previous size, integrating multiple buildings into one unified composition: the Main Shrine Hall (Honden), the Offering Hall (Heiden), the Worship Hall (Haiden), the Purification Hall (Haraedono), and numerous subsidiary structures. The east and west corridors together stretched approximately 275 meters—longer than two and a half football fields. These vermilion-lacquered corridors, supported by pillars rising from the seabed and seeming to glide gracefully over the water’s surface, created a dazzling vista that visitors often compare to a dragon undulating across the waves or a palace floating on the sea itself.

While chief priest Saeki Kagehiro supervised the day-to-day construction work and managed the practical logistics, Kiyomori himself frequently traveled from Kyoto to Miyajima to personally inspect the progress and ensure his vision was being realized. He summoned the most skilled craftsmen and architects from the capital, sparing no expense to ensure the highest quality workmanship. The truly immense costs of this project were funded entirely by the Taira clan’s vast wealth accumulated through Song Dynasty trade, allowing the use of the finest materials and most advanced architectural techniques available in that era.

The Revolutionary Adoption of the Shinden-zukuri Architectural Style

Perhaps the most defining and innovative feature of Kiyomori’s reconstruction project was his bold decision to integrate the shinden-zukuri architectural style into the shrine’s design. Shinden-zukuri was originally developed as the residential architecture of the highest-ranking aristocrats in the Heian capital of Kyoto—it was essentially the architectural language of imperial palaces and noble mansions. Applying this distinctly secular, courtly style to a sacred Shinto shrine built over the sea was groundbreaking, even radical for its time.

The shinden-zukuri style emphasizes elegant symmetry, multiple pavilions and halls linked by covered corridors, and an open, harmonious design that integrates seamlessly with the surrounding natural landscape. At Itsukushima Shrine, Kiyomori adapted these principles to the unique marine setting: the central main hall is flanked by smaller guest shrines and a Noh stage, with all buildings connected by those famous refined walkways. The floorboards of the corridors have strategic gaps between them, allowing seawater to flow freely beneath at high tide. This brilliant engineering solution helps the entire structure withstand the powerful forces of typhoons and tidal surges that regularly sweep through the Seto Inland Sea—the water passes through rather than pushing against solid surfaces.

This architectural choice was far more than merely aesthetic—it was also a calculated cultural and political strategy. By transplanting Kyoto’s most refined architectural aesthetics to this remote island shrine, Kiyomori fashioned a clan sanctuary that visibly embodied and broadcast Taira authority, sophistication, cultural refinement, and far-reaching maritime power across the entire Seto Inland Sea region. When imperial envoys or rival clans visited, they couldn’t help but be impressed by this magnificent synthesis of religious devotion and worldly power.

The Kangen Festival and the Transplanting of Kyoto’s Elegant Performing Arts

Kiyomori’s cultural contributions to Miyajima extended far beyond architecture and physical structures. He actively worked to transplant Kyoto’s most elegant and sophisticated performing arts traditions to the island, creating a living cultural legacy that continues to this day. The Kangen Festival (Kangensai) stands as the signature example of this cultural transfer. Originating in the imperial court of Kyoto, this ritualized form of courtly entertainment—gagaku (ancient court music) performed on boats floating over water—was established at Itsukushima Shrine thanks directly to Kiyomori’s passionate patronage and financial support.

During the annual Kangen Festival, which takes place on the evening of the 17th day of the sixth lunar month, musicians board the beautifully decorated Kangen Boat—an imperial-style barge that evokes the pleasure boats of Heian nobility. They perform traditional gagaku pieces as the boat glides across the moonlit bay toward Jigomae Shrine on the opposite shore of the inlet. The haunting sounds of traditional instruments—the sho (mouth organ), hichiriki (double-reed pipe), and biwa (lute)—floating across the still waters of the Seto Inland Sea create an almost otherworldly atmosphere, transporting listeners back to the refined world of Heian court culture. According to historical records and shrine traditions, when Kiyomori visited Miyajima for these festivals, he would have the shrine’s corridors illuminated with countless torches, creating a magical nighttime spectacle of flickering light reflecting off the water.

Kiyomori also took the initiative to introduce bugaku (court dance accompanied by gagaku music) to Miyajima, importing specific dance traditions from Shitennoji Temple in Osaka. Spectacular dances such as “Ranryo-o” (The Prince of Lanling) and “Nasori” continue to be performed at Itsukushima Shrine to this day, preserving forms that date back over 850 years. Watching dancers in brilliant costumes moving with stylized grace against the dramatic backdrop of the sea and sky, modern visitors can still experience a direct connection to the elegance and refinement of Heian period aristocratic culture that Kiyomori worked so hard to establish on this sacred island.

The Taira Clan’s Legacy, Influence on Itsukushima Worship, and Broader Historical Significance

Itsukushima Shrine as the Taira Clan’s Tutelary Deity and Spiritual Center

Following the grand reconstruction in 1168, Itsukushima Shrine effectively became the Taira clan’s primary tutelary shrine (ujigami)—their spiritual home and the sacred center of clan identity. Taira warriors made pilgrimages to Miyajima before embarking on important military campaigns, praying earnestly for victory and divine protection. They returned after successful battles to give thanks, and marked promotions and other auspicious family events with offerings and celebrations at the shrine. Year by year, through these repeated acts of devotion, the bond between the clan and Itsukushima deepened into something approaching family tradition.

This pattern of devotion was enthusiastically inherited and even intensified by Kiyomori’s eldest son and heir, Taira no Shigemori, who by many accounts was even more pious than his father. Shigemori offered numerous precious treasures to the shrine and played a key role in creating the magnificent Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls. Throughout the Taira clan, the belief took firm root that their continuing prosperity and success in both political and military affairs flowed directly from Itsukushima’s divine protection and blessings.

For the Taira leadership, however, Itsukushima was never merely a sacred focus of worship and spiritual devotion. The shrine also functioned as a vital strategic anchor for maintaining control over the Seto Inland Sea and managing the enormously profitable trade relationship with Song Dynasty China. Commanding the waters around Miyajima meant controlling one of the most strategically important maritime chokepoints in western Japan—and this control underpinned Taira dominance both economically and militarily throughout the region.

Japan–Song Trade Routes and Strategic Control of the Seto Inland Sea

The enormous profits flowing from maritime trade with Song Dynasty China were a key—perhaps the key—reason why Kiyomori prioritized Itsukushima Shrine so heavily. He developed and expanded Owada Harbor (at the site of present-day Kobe Port) and actively promoted overseas commerce, breaking with earlier Japanese policies that had restricted such trade. The Seto Inland Sea functioned as the absolutely vital maritime artery connecting Japan with the Asian continent, and Miyajima—situated near the strategic center of these shipping lanes—was therefore the ideal sacred site from which to pray for safe sea passages and successful commercial ventures.

Song copper coins (especially coins from the Kaiyuan and later eras) imported in massive quantities circulated as currency throughout Japan, accelerating the transition from a rice-based economy to a money-based economy and dramatically increasing the Taira clan’s financial power and flexibility. The trade also brought highly valued luxury goods into Japan: exquisite ceramics and porcelain, fine silks and brocades, aromatic spices, precious medicines and medical texts, Buddhist scriptures, and countless other items that signaled wealth, sophistication, and continental connections. Control of this trade gave the Taira enormous economic advantages over rival clans who lacked similar access to these revenue streams.

In this context, reverence for Itsukushima had a distinctly practical dimension that complemented the spiritual one: prayers for safe voyages and successful trading expeditions weren’t just religious gestures—they were business necessities. Kiyomori entrusted maritime safety to the island’s deity and faithfully returned a substantial portion of his profits as offerings, funding shrine improvements and religious ceremonies. This virtuous cycle—where economic success funded religious devotion, which in turn was believed to ensure continued prosperity—sustained both Taira wealth and power and the ongoing development and beautification of Itsukushima Shrine.

The Fate of Itsukushima Shrine After the Fall of the Taira Clan

The Taira clan met their ultimate defeat at the catastrophic Battle of Dan-no-ura in 1185, the final confrontation of the Genpei War (also called the Jisho–Juei Rebellion). The entire clan leadership perished in the battle or its immediate aftermath, including the child emperor Antoku, who drowned along with many Taira nobles. Despite this complete political annihilation, however, Kiyomori’s magnificent Itsukushima Shrine continued to thrive as a major sacred site—powerful proof that the shrine’s cultural and religious value transcended the political fortunes of any single clan.

Minamoto no Yoritomo, who emerged victorious and established the Kamakura shogunate, notably did not reject or diminish the Taira’s architectural and cultural achievements at Miyajima. Instead, he explicitly recognized Itsukushima’s profound significance to Japanese culture and religion, and made provisions to preserve and protect it. This magnanimous treatment demonstrates that the shrine had become something larger than a mere Taira clan monument—it had become an irreplaceable part of Japan’s cultural heritage that transcended political rivalries.

The shrine did face significant challenges in subsequent centuries. Devastating fires in 1207 and 1223 destroyed the main buildings, requiring extensive reconstruction. Many of the current structures actually date from after the Ninji era (1240–1243), roughly 70 years after Kiyomori’s death. However, these rebuilding efforts carefully followed Kiyomori’s original design and layout—his architectural vision proved so successful and beloved that later generations saw no reason to alter it fundamentally.

During Japan’s turbulent Sengoku (Warring States) period, the powerful warlord Mori Motonari undertook a major restoration of Itsukushima Shrine after his famous victory at the Battle of Itsukushima in 1555. In the more stable Edo period, the Asano clan, lords of Hiroshima domain, served as the shrine’s official protectors and sponsors. Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese state has taken responsibility for safeguarding this national treasure. Through all these political transformations, the tradition of worship that Taira no Kiyomori initiated over 850 years ago has been carefully handed down, generation after generation, to the present day.

The Enduring Value of Kiyomori’s Legacy in the Modern World

The magnificent floating shrine complex that Taira no Kiyomori created in 1168 continues to captivate travelers from every corner of the world more than 850 years later. When you visit Miyajima shrine today and see those famous vermilion corridors stretching over the waves, you’re witnessing Kiyomori’s vision made real—a vision so powerful and beautiful that it has endured across centuries of wars, fires, and political upheavals. In December 1996, Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima was registered as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site, earning international recognition for the exceptional architectural beauty and profound cultural value that Kiyomori helped create.

Kiyomori’s legacy extends far beyond the physical buildings and structures, as impressive as they are. The intangible cultural traditions he fostered on Miyajima—particularly the Kangen Festival and bugaku court dances—continue to thrive today, performed much as they were in the 12th century. At the annual Kangen Festival, held on the evening of the 17th day of the sixth lunar month (usually in July or August by the modern calendar), those same timeless gagaku melodies drift across the Seto Inland Sea, creating a direct sensory connection between modern visitors and the elegant world of the Heian era that Kiyomori loved.

The precious treasures directly tied to Kiyomori and his family, including the incomparable Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls, are carefully preserved and displayed at the Itsukushima Shrine Treasure Museum (Homotsukan). These National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties illuminate not only the splendor and wealth of the Taira clan at their height, but also Kiyomori’s refined aesthetic taste and his sophisticated understanding of how to blend religious devotion with political messaging. The world of Itsukushima Shrine—where faith, politics, economy, art, and culture all converged under the patronage of one visionary samurai—continues to stand as an enduring symbol of the remarkable depth, complexity, and adaptability of Japanese civilization.

Frequently Asked Questions About Taira no Kiyomori and Itsukushima Shrine

Why did Taira no Kiyomori choose to rebuild Itsukushima Shrine on such a grand scale?

Kiyomori had multiple interconnected motives for his massive investment in Itsukushima Shrine. First and most practically, Miyajima occupied a strategically crucial position as a base for controlling the vital Seto Inland Sea shipping lanes and for managing the enormously profitable trade with Song Dynasty China. Second, after receiving a divine revelation in a dream during his pilgrimage to Mount Koya, he became a devoted believer in Itsukushima’s deity and genuinely believed his rise to power had been divinely granted. Third, he needed a powerful symbolic focus—a grand clan shrine—to help unify the far-flung Taira family members and vassals around a shared spiritual and cultural identity. Military strategy, economic interests, religious devotion, and political ambition all converged and intertwined at Miyajima, making it the perfect site for Kiyomori’s greatest project.

Are the shrine buildings that Taira no Kiyomori originally constructed still standing today?

Unfortunately, no—the original buildings that Kiyomori sponsored and oversaw in 1168 were destroyed by catastrophic fires in 1207 and 1223. The main shrine structures that visitors see today were reconstructed after the Ninji era (beginning around 1240–1243), roughly 70 years after Kiyomori’s death. However, it’s important to note that the basic architectural layout, overall design philosophy, and the distinctive shinden-zukuri style all faithfully follow Kiyomori’s original vision and plans. The rebuilders clearly recognized the brilliance of his design and saw no reason to change it fundamentally. So while the physical wood and materials aren’t original, the essential character and appearance of the shrine complex preserve the image of the magnificent maritime shrine that Kiyomori first envisioned and created.

Can visitors actually see the famous Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls?

The original Heike Nōkyō scrolls are designated National Treasures of Japan, which means they must be carefully protected and preserved for future generations. Because of their age and fragility, beautiful replicas are typically on display at the Itsukushima Shrine Treasure Museum (Homotsukan) year-round, allowing visitors to appreciate the artistry and devotion that went into creating them. The actual original scrolls are exhibited to the public only during special viewing periods, generally in spring and autumn when temperature and humidity conditions are most stable. Occasionally, selections from the collection may also appear at major special exhibitions organized by prestigious institutions such as the Tokyo National Museum or Kyoto National Museum. If you’re particularly interested in seeing the originals and are planning a trip to Miyajima, it’s worth checking exhibition schedules in advance—seeing these masterpieces in person is truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

When and how did the relationship between Taira no Kiyomori and Itsukushima Shrine begin?

The relationship began when Kiyomori was appointed Governor of Aki Province in the second year of the Kyuan era (1146), at age 29. This appointment gave him jurisdiction over the region including Miyajima and sparked his initial interest in the shrine. His first documented pilgrimage to Itsukushima Shrine took place in August of Eiryaku 3 (1160), shortly after his decisive victory in the Heiji Rebellion. He then orchestrated the magnificent dedication of the Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls in Chokan 2 (1164), and finally completed the large-scale reconstruction of the shrine buildings in Ni’an 3 (1168). Over the course of approximately 22 years, from his initial appointment through the completion of construction, Kiyomori progressively deepened his ties with Itsukushima Shrine, transforming it from one sacred site among many into the spiritual and cultural center of Taira clan identity.

What specific aspects of Kyoto’s aristocratic culture did Kiyomori introduce to Miyajima?

Kiyomori worked systematically to transplant multiple elements of Heian capital culture to Miyajima. The highlights include: the Kangen Festival (Kangensai)—the tradition of performing ritualized court music (gagaku) on decorated boats floating over the water; bugaku—elegant court dances accompanied by gagaku music, including specific pieces like “Ranryo-o” (The Prince of Lanling) and “Nasori” that were transmitted from Shitennoji Temple in Osaka; the shinden-zukuri architectural style—the sophisticated palace architecture of Kyoto aristocrats, adapted for a shrine setting; and the refined art of creating gorgeously decorated sutra scrolls, exemplified by the Heike Nōkyō collection. Collectively, these cultural elements represent the absolute pinnacle of Heian period aristocratic culture and reflect the lively cultural exchange that flowed back and forth between Kyoto and the Seto Inland Sea region during Taira dominance.

What happened to Itsukushima Shrine after the Taira clan’s catastrophic downfall?

Despite the complete destruction of the Taira clan at the Battle of Dan-no-ura in 1185, Itsukushima Shrine continued to be protected and valued by successive military and political leaders, beginning with the victorious Minamoto clan. Minamoto no Yoritomo, founder of the Kamakura shogunate, explicitly recognized the shrine’s cultural and religious importance and made provisions to preserve and protect it—demonstrating that its value transcended clan politics. In the turbulent Sengoku period (1467–1615), the powerful warlord Mori Motonari undertook a major restoration after his victory at the Battle of Itsukushima in 1555. During the peaceful Edo period (1603–1868), the Asano clan, lords of Hiroshima domain, served as the shrine’s official protectors and sponsors. Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government has taken responsibility for safeguarding Itsukushima Shrine as a priceless national treasure. Though the Heike regime fell and the clan was annihilated, the extraordinary cultural value of the shrine that Kiyomori created has been carefully and continuously passed down through the centuries to our own time.

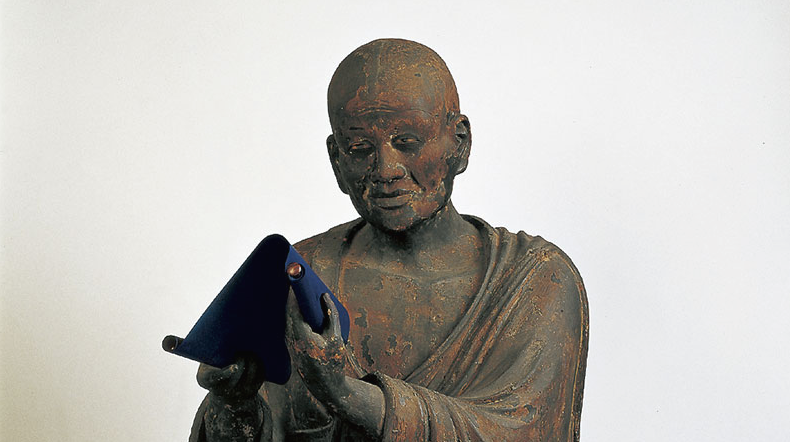

Where can visitors see statues or images of Taira no Kiyomori on Miyajima?

About a 3-minute walk from Miyajima Pier in the direction of Itsukushima Shrine, you’ll find an impressive bronze statue of Taira no Kiyomori that was erected in March 2014 (Heisei 26). The statue was created to commemorate the 830th anniversary of Kiyomori’s death and depicts him in the formal court robes befitting his position as Grand Minister of State. Local tradition says the statue faces toward Kyoto, the capital where Kiyomori spent much of his life and wielded his power. The statue has become a popular photo spot for visitors interested in Miyajima shrine history. Additionally, if you’re ever in Kyoto, you can see an Important Cultural Property: a wooden seated statue of Taira no Kiyomori from the Kamakura period, preserved at Rokuharamitsu-ji Temple in the Higashiyama district—this is one of the few surviving portrait sculptures of Kiyomori from the medieval period and offers a fascinating glimpse into how he was remembered by later generations.

Summary

The grand reconstruction of Itsukushima Shrine undertaken by Taira no Kiyomori in 1168 was far more than simply another chapter in Japanese architectural history—it marked a genuine turning point in the nation’s political evolution, economic development, and cultural sophistication. Having secured firm control of the strategically vital Seto Inland Sea and amassed vast wealth from flourishing trade with Song Dynasty China, Kiyomori channeled this accumulated power, resources, and ambition into creating Miyajima’s magnificent floating shrine complex.

The rich cultural legacy he fostered during his decades of devotion to the island—the elegant shinden-zukuri architectural layout that harmonizes palace and shrine traditions, the dedication of the incomparable Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls, and the establishment of refined performing arts traditions like kangen music and bugaku court dance—still animate and define Itsukushima Shrine more than 850 years later. Although the Taira clan fell dramatically and met a tragic end at Dan-no-ura, the extraordinary shrine that Kiyomori envisioned has been lovingly cherished and meticulously preserved across the centuries by successive generations of Japanese, earning UNESCO World Heritage status in 1996 as recognition of its universal cultural value.

When you visit Miyajima today and walk along those famous vermilion corridors stretching over the shimmering waters of the Seto Inland Sea, take a moment to pause and imagine Kiyomori’s original dream—his bold vision of fusing maritime power, spiritual devotion, cultural refinement, and political ambition into one breathtaking monument. Feel the passion, strategic brilliance, and aesthetic sensibility that set this magnificent sea shrine shimmering upon the tides more than eight centuries ago. That’s the enduring gift that Taira no Kiyomori gave not just to Miyajima, but to all of us who are lucky enough to experience this remarkable place.

References & Sources

- Cultural Heritage Online: Itsukushima Shrine: Main Hall, Heiden Hall, Haiden Hall

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website: History

- Miyajima Tourism Association: Itsukushima Shrine

- WANDER National Treasures: National Treasures – Paintings | Heike Nōkyō

- Rokuharamitsu-ji Temple: Temple Treasures

- Hiroshima Cultural Encyclopedia: Hiroshima’s Cornerstone “The Heike and Itsukushima Culture”

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, Miyajima Town History: General History Volume, Miyajima Town, 1992

- Fukuyama Toshio, Architecture of Itsukushima Shrine, Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 1988

- Nishi Kazuo, Architectural History of Itsukushima Shrine, Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2005

- Komatsu Shigemi, Research on the Heike Nōkyō, Kodansha, 1996