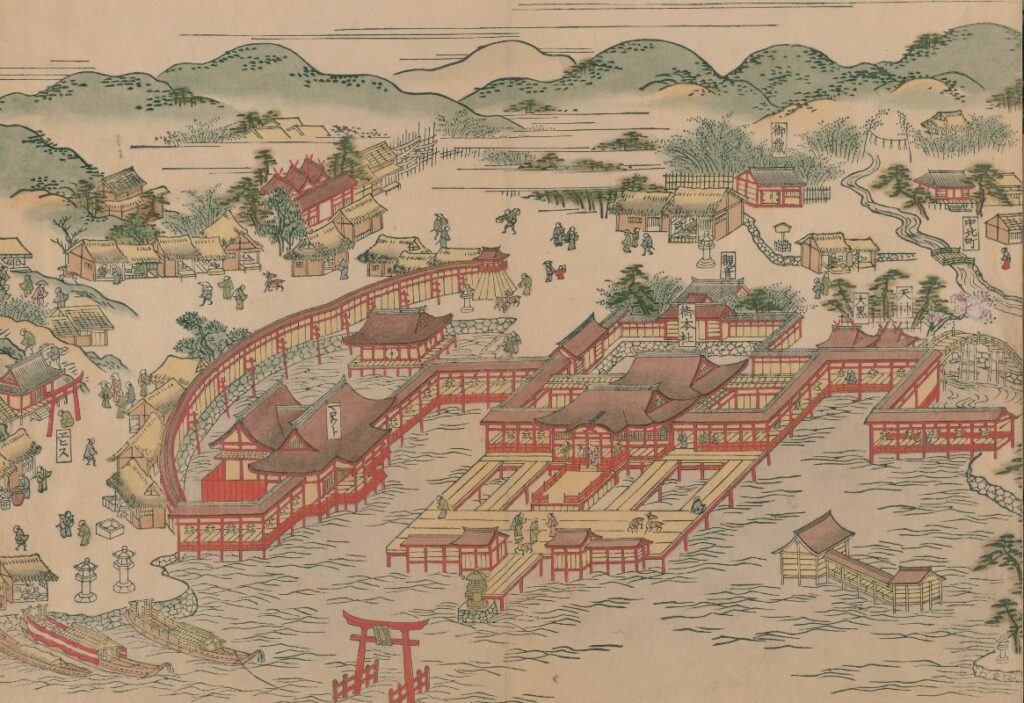

Miyajima, located in distant Aki Province (present-day Hiroshima Prefecture) far from Kyoto, is a divine island floating in the Seto Inland Sea. During the Heian period, it held special religious significance for aristocrats in the capital and became a celebrated destination for pilgrimage from Kyoto.

The relationship between Heian nobles and Miyajima went far beyond a simple visit to a provincial shrine. Regent families such as the Fujiwara, retired emperors during the Insei period, and the Heike clan all competed to make pilgrimages and present lavish offerings at Itsukushima Shrine. This article explores the history and nature of their devotion—why the nobility of the capital revered Miyajima—and how that legacy still shapes Miyajima travel and cultural tourism today.

The Historical Development of Heian Aristocrats and Miyajima Worship

Early Heian Period: Shinto-Buddhist Syncretism and Miyajima’s Rising Status

In the early Heian period, Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima gradually drew the attention of the central aristocracy, driven by the spread of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism. The deity enshrined at Itsukushima Shrine, Princess Ichikishima-hime, came to be identified with the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten.

Benzaiten—goddess of music, eloquence, and wealth—was especially popular among the Heian nobility. Members of the regent houses, particularly the Fujiwara clan, sought her protection to maintain political authority and household prosperity. Miyajima’s position as the “First Shrine of Aki Province” reflected this rising fervor. The Engishiki, compiled in 905, records Itsukushima Shrine as a “Myojin Taisha” (Great Shrine of the Divine Spirit), signaling special importance to the imperial court and recognition of Miyajima’s stature among Kyoto’s elites.

Regent Period: The Fujiwara Clan’s Devotion

During the 10th–11th centuries, when regent politics dominated, the Fujiwara clan deepened their devotion to Miyajima. As regents and kanpaku (chief ministers), they prioritized political stability and the flourishing of their lineage, turning to Miyajima’s deity—understood as Benzaiten—for divine support.

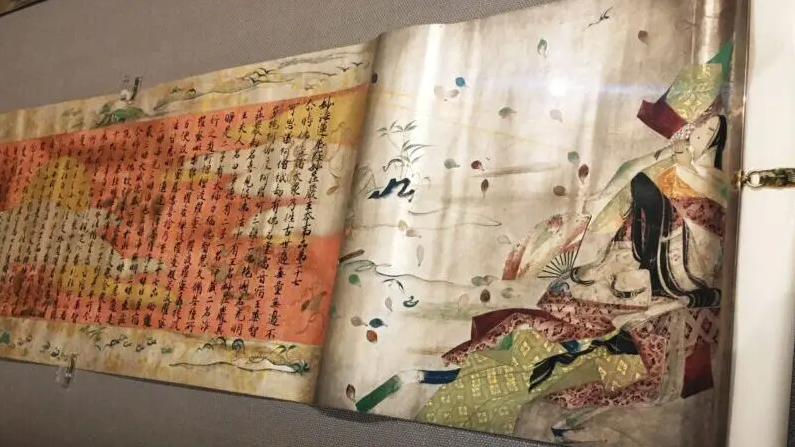

High-ranking aristocrats often dispatched proxy worshippers to Miyajima and presented lavish dedications. Long-distance travel from Kyoto was arduous, so entrusting the journey to reliable retainers was common practice. Offerings ranged from sutra scrolls and ritual implements to military equipment and finely crafted furnishings—objects that mirrored the taste and sophistication of courtly culture.

The Insei Period: Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Reverence for Miyajima

With the advent of the Insei period in the 12th century, faith in Miyajima flourished further. Emperor Go-Shirakawa is particularly known for his deep reverence. Even before ascending the throne in 1156 (Hogen 1), he showed interest in Itsukushima Shrine.

One reason for the Emperor’s esteem was the influence of Taira no Kiyomori. As Governor of Aki Province, Kiyomori developed Miyajima and conveyed its splendor to the court. It is thought that the Emperor, through Kiyomori, made offerings to elevate the shrine’s authority and, by extension, support the Taira government. While Go-Shirakawa was famously devoted to the Kumano faith, Miyajima was regarded as the “Kumano of the Sea.” A vital node for maritime travel, it was an ideal place to pray for the safety of sea routes to Japan’s western provinces—an intention that blended piety with political strategy.

The Reality of Heian Aristocrats’ Pilgrimages to Miyajima

Pilgrimage Routes from the Capital to Miyajima

The journey from Heian-kyo (Kyoto) to Miyajima was long, combining overland and sea travel. Pilgrims typically followed the Sanyo Road westward from Kyoto to Tomonoura in Bingo Province (present-day eastern Hiroshima Prefecture). From there, they transferred to boats and crossed the Seto Inland Sea.

Tomonoura, a classic tide-waiting port, required travelers to await favorable currents before sailing west with the tide. En route, they paused at harbors such as Murozumi in Suo Province (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture) and eventually entered Itsukushima Bay opposite the island. Weather and seasonal winds could significantly prolong the trip. For this reason, high-ranking nobles rarely made the journey themselves, often appointing trusted proxies to perform the rites and deliver offerings on their behalf. Upon arrival, pilgrims underwent shore purification (misogi), then proceeded to the shrine to present heihaku (sacred offerings) and recite norito (prayers). Proxy worshippers read prayers in their patrons’ names and formally presented the dedications.

The offerings commonly consisted of sutra scrolls, alongside mirrors, swords, horse tack, and silk textiles—luxurious objects that reflected the refined aesthetic of Heian aristocratic culture. Some of these gifts remain preserved at Itsukushima Shrine today and are designated as National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties.

The Many Dedicated Cultural Treasures

The items dedicated to Miyajima by Heian nobles represent the pinnacle of courtly culture. The most famous example is the “Heike Nokyo” sutras, dedicated by Taira no Kiyomori in 1167. Transcribing the Lotus Sutra and related texts, members of the Taira clan created an opulent masterpiece renowned for its lavish decoration.

Also significant is the “Kunoji Sutra,” a complete set of Buddhist scriptures transcribed in the late Heian period by nobles including the Fujiwara, embellished with vivid pigments and precious materials. Now designated a National Treasure and housed in the Treasure Hall of Itsukushima Shrine, it exemplifies the grandeur of Heian artistry. Among military accoutrements, extravagant offerings such as the “Gilded Bronze Saddle with Cloud-and-Pearl Ornaments and Openwork Carving” prioritized ornament over practicality—simultaneously honoring the deity and displaying the donor’s wealth and rank.

The Historical Significance of Heian Aristocrats’ Worship at Miyajima

Heian-period worship at Miyajima was not only a religious phenomenon; it also carried political, economic, and cultural significance. Politically, aristocrats in Kyoto strengthened their reach into the provinces by supporting influential local shrines. Aki Province—home to Miyajima—was a strategic maritime hub in the Seto Inland Sea, critical to maintaining influence across western Japan. The Fujiwara and Taira clans valued Miyajima for precisely these reasons.

Economically, waves of offerings and ritual traffic brought significant wealth to Miyajima. The influx of pilgrims boosted the local economy, while the expansion of shrine lands increased Itsukushima Shrine’s economic power within Aki Province. Culturally, Kyoto’s refined court aesthetics traveled westward via Miyajima; donated sutras and artworks elevated provincial cultural standards, and the island emerged as a hub of exchange linking Kyoto with the western regions.

The Enduring Value of Heian Aristocratic Faith in the Modern Era

The Heian aristocracy’s devotion to Miyajima continues to resonate today. Many National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties preserved at Itsukushima Shrine were originally dedicated by Heian nobles. These works are indispensable to understanding Japanese history and culture and form a highlight of cultural tourism for visitors interested in Miyajima history and the legacy of Itsukushima Shrine.

Foremost among them, the Heike Nokyo—often regarded as the supreme masterpiece of Heian decorated sutras—holds an exceptional place in art history. Each year, researchers and culture lovers visit Miyajima to experience these treasures and encounter the world of Heian aristocratic faith. The traditional route from Kyoto to Miyajima also continues to inspire travelers seeking to retrace historic pilgrimage paths across the Seto Inland Sea and feel the reverence that once drew nobles to this sacred island.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Heian nobles worship at the distant Miyajima?

Because Ichikishimahime-no-Mikoto, the deity of Itsukushima Shrine, was identified with the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten—beloved by Heian nobles as the patron of music, eloquence, and wealth. Miyajima’s strategic position on the Seto Inland Sea also made it a key maritime hub, aligning religious devotion with political aims to maintain influence over western Japan.

Did the Fujiwara clan actually visit Miyajima?

Few records show high-ranking Fujiwara regents and kanpaku traveling personally; most appointed trusted retainers as proxies. The one-way journey from Kyoto to Miyajima typically took 10 days to two weeks, making frequent personal visits by top nobles impractical.

What was Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s relationship with Miyajima?

Emperor Go-Shirakawa held deep reverence for Miyajima and made numerous offerings through Taira no Kiyomori. While he was also devoted to the Kumano faith, he regarded Miyajima as the “Kumano of the Sea,” a sacred site for prayers for safe maritime travel to the western provinces. This devotion likely served political ends as well, reinforcing the Taira-led order.

Are any of the cultural assets donated by Heian nobles still preserved today?

Yes, many cultural assets are preserved at Itsukushima Shrine today. The most famous is the National Treasure “Heike Nokyo” sutra set dedicated by Taira no Kiyomori. Other precious items—sutras, mirrors, swords, and horse tack—also survive, with selected works on display at Miyajima’s Treasure Hall for visitors interested in Japanese cultural heritage and Miyajima history.

What route did pilgrims take from the capital to Miyajima?

Travelers went west from Kyoto along the Sanyo Road to Tomonoura in Bingo Province, then continued by boat across the Seto Inland Sea. Pilgrims waited at Tomonoura for favorable tides, resting at ports such as Murozumi in Suo Province before entering Itsukushima Bay. Even under good conditions, the one-way journey took 10 days to two weeks.

How did Shinto-Buddhist syncretism influence the faith at Miyajima?

Through syncretism, Ichikishimahime-no-Mikoto was identified with Benzaiten, creating a distinctive system of worship centered on a Shinto shrine while incorporating Buddhist elements. This fusion appealed to Heian elites and remains a hallmark of Japan’s religious culture, where Shinto and Buddhism have long coexisted.

Summary

For Heian nobles, Miyajima was far more than a provincial shrine—it was a crucial locus of faith where politics, economics, and culture intersected. The Fujiwara regent houses, Emperor Go-Shirakawa, and the Taira clan all vied to honor Itsukushima Shrine with sumptuous offerings.

Many of these dedications—transported by proxy pilgrims after journeys of over ten days each way—are preserved at Itsukushima Shrine as National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties. They testify to the depth of Heian devotion and the refinement of courtly culture. Rooted in Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, the faith uniting Princess Ichikishimahime and Benzaiten at Miyajima stands as a vivid symbol of Japanese religious culture.

The political, economic, and cultural significance of Heian-era worship at Miyajima still offers rich insights today. Visiting the cultural properties of Itsukushima Shrine is a meaningful way to rediscover the reverence felt by Heian nobles and appreciate the enduring value of the heritage they left behind.

References & Sources

- Agency for Cultural Affairs Cultural Heritage Online: Itsukushima Shrine (World Heritage Site)

- Agency for Cultural Affairs National Designated Cultural Properties Database: Itsukushima Shrine

- Hiroshima Prefectural Board of Education Cultural Properties Division

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website: History

- Miyajima Tourism Association: World Cultural Heritage Registration

- Nara National Museum: Itsukushima Shrine National Treasures Exhibition

- Hiroshima Prefectural University Miyajima Studies Center

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, Miyajima Town History: General History Volume, Miyajima Town, 1992

- Fumihiko Gomi, Research on the Insei Period Society, Yamakawa Publishing, 1984

- Yasuo Motoki, Taira no Kiyomori and Emperor Go-Shirakawa, Kadokawa Shoten, 2012

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Itsukushima Shinto Shrine