In the late Heian period, one warrior reshaped Itsukushima Shrine and, with it, charted a new course for Japan. That man was Taira no Kiyomori, the first samurai to attain the rank of Grand Minister of State.

In 1168, Taira no Kiyomori rebuilt Itsukushima Shrine into the breathtaking “floating shrine” you see today on Miyajima. This was far more than a routine restoration. It was a monumental statement of Taira power—rooted in mastery of the Seto Inland Sea and enormous wealth from trade with Song China. Kiyomori’s choice of Miyajima fused military strategy, religious devotion, and political ambition into one visionary project.

The Historical Background of Taira no Kiyomori and Itsukushima Shrine

His Appointment as Governor of Aki and His Encounter with Miyajima

Taira no Kiyomori began forging a deep connection with Itsukushima Shrine in the second year of the Kyuan era (1146), when he was appointed Governor of Aki Province at the age of 29. Aki corresponded to the western part of present-day Hiroshima Prefecture and was a crucial hub for maritime traffic on the Seto Inland Sea. This regional appointment would profoundly alter both Kiyomori’s life and the destiny of the Taira clan.

As Governor of Aki, Kiyomori consolidated control over Seto Inland Sea routes and amassed immense wealth through maritime trade. The Inland Sea was especially vital as a corridor linking Japan with Song China. By effectively controlling this waterway, Kiyomori dramatically expanded the Heike clan’s economic base. Imports from Song—copper coins, ceramics, books, medicines, and more—had a transformative impact on Japan at the time.

According to The Tale of the Heike, when Kiyomori visited Mount Koya, a monk gave him a prophecy: “If you build Itsukushima Shrine, you will surely attain the highest rank.” This oracle, combined with Kiyomori’s deep faith, cemented his devotion to Itsukushima.

First Pilgrimage in Eiryaku 3 and Deepening Devotion

Kiyomori made his first pilgrimage to Itsukushima Shrine in August of Eiryaku 3 (1160), just after the Heiji Rebellion, where he defeated Minamoto no Yoshitomo and secured Taira supremacy. That same year, he rose to Junior Third Rank, joining the court nobility. Amid this turbulence, he offered thanks to the deity of Itsukushima for victory.

After that first visit, Kiyomori’s devotion deepened. He formed close ties with the chief priest, Saeki Kagehiro, forging a special bond between the Taira clan and Itsukushima Shrine. Kiyomori visited Miyajima several times a year and brought refined Kyoto culture to the island, dedicating musical performances during his pilgrimages.

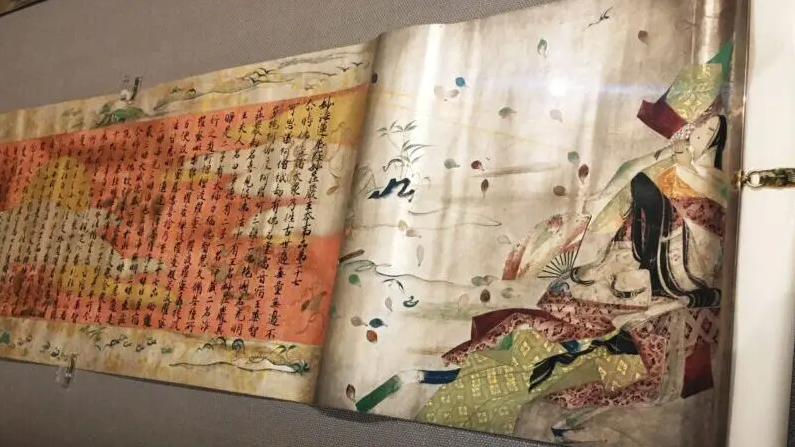

The Taira Clan’s Offering of Sutra Copies in 1164

The peak of Kiyomori’s devotion came with the Taira clan’s lavish dedication of sutra scrolls in September 1164. It began with a prayer text penned by Kiyomori himself, followed by contributions from Taira no Shigemori, Taira no Yoritomo, and Taira no Norimori. In total, 33 volumes were offered, including the 28 chapters of the Lotus Sutra, the Sutra of Opening and Closing, the Amitabha Sutra, and the Heart Sutra—each volume transcribed by a different Taira family member.

The decoration of these scrolls represented the finest craftsmanship of the day, with scattered gold and silver leaf, brilliant underdrawings, and exquisite patterns. Every element—covers, endpapers, paper, metal fittings, cords, and scroll rods—reflected the Heike’s wealth and aesthetic sensibility. Legend even claims Kiyomori used ink mixed with his own blood, a dramatic symbol of his devotion.

The chosen number, 33, reflects the Thirty-Three Manifestations of the Eleven-Faced Kannon, the principal deity of Itsukushima. Kiyomori prayed for prosperity in this life and the next, offering the highest tribute to the deities and buddhas of Itsukushima. Known as the Heike Nōkyō, the collection is now designated a National Treasure and acclaimed worldwide as the supreme masterpiece of Japanese decorated sutras.

Characteristics and Technical Details of the Shrine Construction

The Large-Scale Construction of 1168

Kiyomori rebuilt Itsukushima Shrine in the third year of the Ni’an era (1168). At 51, he already held the highest office in the land: Junior First Rank, Grand Minister of State. He believed this unprecedented achievement for a samurai was granted through Itsukushima’s divine protection.

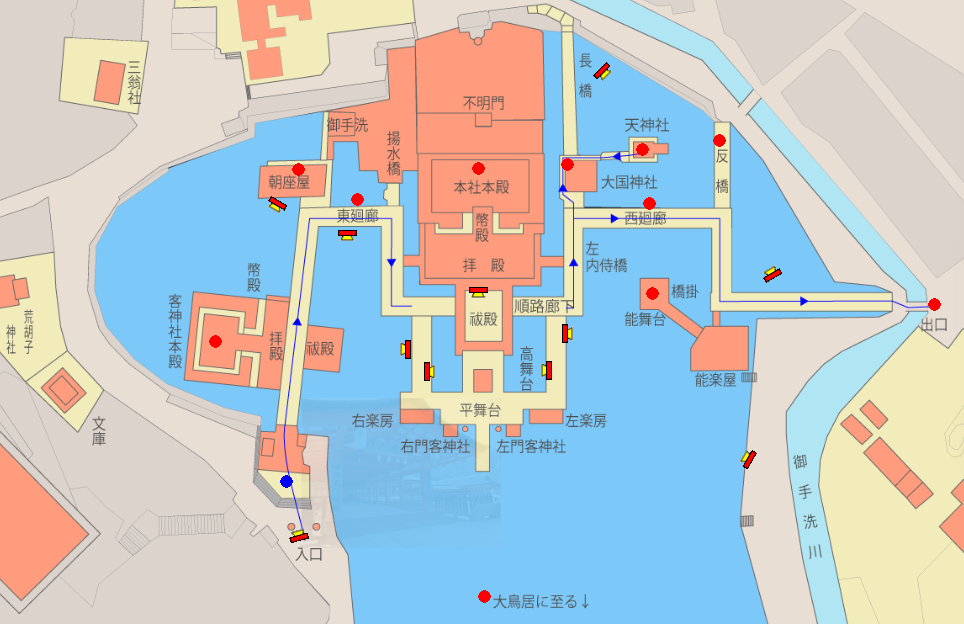

The reconstruction transformed a modest waterfront shrine into the awe-inspiring maritime complex known worldwide today. The precincts expanded severalfold, integrating the Main Shrine Hall, Offering Hall (Heiden), Worship Hall (Haiden), and Purification Hall into a grand, unified composition. The east and west corridors together stretched about 275 meters. Vermilion-lacquered corridors gliding over the sea created a dazzling vista—like a dragon undulating across the water’s surface.

While chief priest Saeki Kagehiro supervised day-to-day work, Kiyomori frequently traveled to Miyajima to inspect progress and summoned elite craftsmen from Kyoto. The immense costs were funded by the Taira clan’s wealth from Song-dynasty trade, allowing the use of the finest materials and techniques of the era.

Adoption of the Shinden-zukuri Style

The defining feature of Kiyomori’s project was the integration of the shinden-zukuri style—originally the aristocratic residential architecture of the Heian capital—into a sacred shrine. This was bold and groundbreaking: applying a secular courtly style to a holy site in the sea.

Shinden-zukuri emphasizes symmetry, multiple halls linked by corridors, and an open design in harmony with nature. At Itsukushima Shrine, the central main hall is flanked by guest shrines and a Noh stage, all connected with refined walkways. Gapped floorboards allow seawater to flow beneath at high tide, helping the structure withstand typhoons and tidal surges.

This architectural choice was also a cultural strategy. By transplanting Kyoto’s refined aesthetics to Miyajima, Kiyomori fashioned a clan shrine that visibly embodied Taira authority, sophistication, and maritime reach across the Seto Inland Sea.

The Kangen Festival and the Spread of Kyoto Culture

Kiyomori did more than build halls; he carried Kyoto’s elegant performing arts to Miyajima. The Kangen Festival is the signature example. Originating in the capital, this ritualized courtly entertainment—gagaku performed on the water—was established at Itsukushima Shrine thanks to Kiyomori’s patronage.

During the Kangen Festival, musicians board the Kangen Boat (an imperial-style barge) and perform across the moonlit bay toward Jigomae Shrine on the opposite shore. The sounds of the sho, hichiriki, and biwa floating over the Seto Inland Sea brought the essence of aristocratic culture to Miyajima. Traditions say that when Kiyomori visited, he illuminated the corridors with torches and enjoyed the evening spectacles.

Kiyomori also introduced bugaku (court dance) from Shitennoji Temple in Osaka. Dances such as “Ranryo-o” and “Nasori” continue at Itsukushima Shrine today. Dancers in brilliant costumes moving against a backdrop of sea and sky preserve the grace of Heian culture for modern visitors.

The Heike Clan, Its Influence on Itsukushima Worship, and Historical Significance

Itsukushima Shrine as the Heike Clan’s Guardian Deity

After the grand reconstruction, Itsukushima Shrine became the Taira clan’s tutelary shrine. Heike warriors visited before pivotal campaigns to pray for victory and returned to give thanks for promotions and auspicious events. Year by year, the bond between the clan and Itsukushima deepened.

Devotion to the shrine was inherited by Kiyomori’s heir, Taira no Shigemori, who was even more pious. He offered many treasures and helped copy the Heike Nōkyō, reinforcing the belief that Taira prosperity flowed from Itsukushima’s divine protection.

For the Heike, Itsukushima was not only a sacred focus of worship. It was also a strategic anchor for controlling the Seto Inland Sea and managing Japan–Song trade. Commanding the waters around Miyajima underpinned Taira dominance—economically and militarily.

Source: WANDER National Treasure

Japan–Song Trade and Control of the Seto Inland Sea

The enormous profits from trade with Song China were a key reason Kiyomori prioritized Itsukushima Shrine. He developed Owada Harbor (present-day Kobe Port) and actively promoted overseas commerce. The Seto Inland Sea was the vital artery connecting Japan to the continent, and Miyajima—situated near its strategic center—was the ideal sacred site to pray for safe sea-lanes.

Song copper coins imported in bulk circulated as currency within Japan, accelerating a money economy and dramatically increasing Taira financial power. Trade also brought luxury goods—ceramics, silks, spices, and medicines—that signaled the clan’s wealth and authority.

In this sense, reverence for Itsukushima had a practical dimension: prayers for safe voyages and successful trade. Kiyomori entrusted maritime safety to the island’s deity and returned a share of his profits as offerings. This cycle of economy and faith sustained both Taira prosperity and the development of Itsukushima Shrine.

Itsukushima Shrine After the Heike Clan’s Fall

The Heike were defeated at the Battle of Dan-no-ura during the Jisho–Juei Rebellion (Genpei War). Even so, Kiyomori’s Itsukushima Shrine continued as a major sacred site. Minamoto no Yoritomo did not reject Taira achievements; he recognized Itsukushima’s significance and preserved it—proof that the shrine’s cultural value transcended political rivalry.

In the Kamakura period, fires in 1207 and 1223 destroyed the buildings, but they were rebuilt each time. Many current structures date to after the Ninji era (1240–1243), yet the overall layout and style follow Kiyomori’s plan—his vision lives on in enduring form.

In the Sengoku era, Mori Motonari, after his victory at the Battle of Itsukushima, undertook a large restoration. In the Edo period, the Asano lords of Hiroshima protected the shrine. Since the Meiji era, it has been safeguarded by the state. The tradition of worship initiated by Kiyomori has been handed down to the present day.

The Value of Kiyomori’s Legacy Passed Down to the Present Day

The floating shrine complex created by Taira no Kiyomori in 1168 still captivates travelers from around the world more than 850 years later. In December 1996, Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima was registered as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site—international recognition of the architectural beauty and cultural value Kiyomori helped shape.

Kiyomori’s legacy is not only architectural. Intangible traditions like the Kangen Festival and bugaku court dance—arts he fostered on Miyajima—continue today. At the annual Kangen Festival, held on the 17th day of the sixth lunar month, timeless gagaku melodies drift over the Seto Inland Sea, connecting visitors to the elegance of the Heian era.

Treasures tied to Kiyomori, including the Heike Nōkyō sutra scrolls, are carefully preserved at the Itsukushima Shrine Treasure Museum. These National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties illuminate the splendor of the Taira and Kiyomori’s refined taste. The world of Itsukushima Shrine—where faith, politics, economy, and culture converged under a samurai patron—continues to stand as a symbol of the depth and diversity of Japanese culture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Taira no Kiyomori build Itsukushima Shrine?

Kiyomori had several motives. First, Miyajima was crucial as a base for controlling the Seto Inland Sea and for Japan–Song trade. Second, after receiving a divine revelation in a dream at Mount Koya, he became a devoted believer in Itsukushima’s deity. Third, he needed a symbolic focus to unify the Taira clan around a powerful ancestral shrine. Military, economic, religious, and political aims intertwined on Miyajima.

Are the shrine buildings constructed by Taira no Kiyomori still standing today?

Unfortunately, the buildings Kiyomori sponsored in 1168 were destroyed by fires in 1207 and 1223. The current halls were reconstructed after the Ninji era (1240–1243). However, the basic layout and style follow Kiyomori’s design, preserving the image of the maritime shrine he envisioned.

Can I actually see the Heike Nōkyō?

The original Heike Nōkyō is a National Treasure. Typically, a replica is on display at the Itsukushima Shrine Treasure Museum. The originals are shown only during special viewings, generally in spring and autumn. They may also appear at special exhibitions at institutions such as the Tokyo National Museum or Kyoto National Museum. Check exhibition schedules in advance if you’re planning a trip to Miyajima.

When did the relationship between Taira no Kiyomori and Itsukushima Shrine begin?

The relationship began when Kiyomori was appointed Governor of Aki in the second year of the Kyuan era (1146). His first pilgrimage took place in August of Eiryaku 3 (1160). He then dedicated the Heike Nōkyō in Chokan 2 (1164) and completed large-scale construction in Ni’an 3 (1168). Over roughly 22 years, Kiyomori deepened his ties with Itsukushima Shrine.

What aspects of Kyoto culture did Kiyomori introduce to Miyajima?

Highlights include the Kangen-sai (ritualized court music performed on the water), bugaku (court dance and music, including pieces like “Ranryo-o” and “Nasori” transmitted from Shitenno-ji Temple in Osaka), the shinden-zukuri architectural style, and the art of decorated sutras. These represent the pinnacle of Heian aristocratic culture and reflect lively cultural exchange between Kyoto and the Seto Inland Sea.

What happened to Itsukushima Shrine after the Heike clan’s downfall?

Itsukushima Shrine continued to be protected by successive rulers, beginning with the Minamoto, even after the Heike defeat. Minamoto no Yoritomo valued the shrine and preserved it. In the Sengoku era, Mori Motonari restored it; in the Edo period, the Asano clan protected it; and since the Meiji era, the state has safeguarded it. Though the Heike regime fell, the cultural value of Itsukushima—shaped by Kiyomori—has been carefully passed down.

Where can I see the statue of Kiyomori on Miyajima?

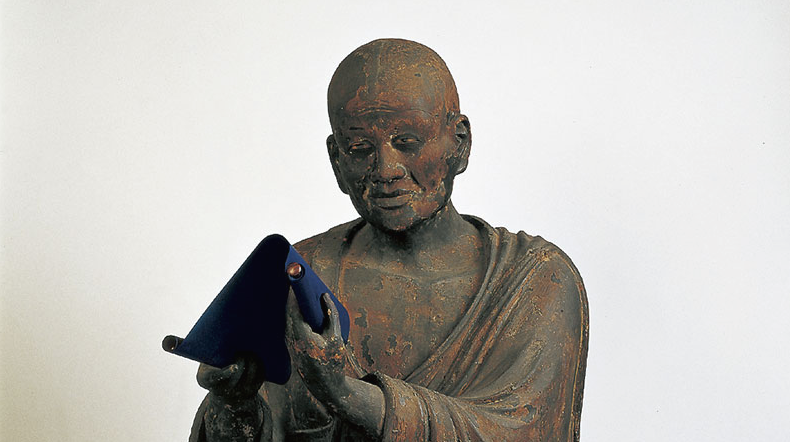

About a 3-minute walk from Miyajima Pier toward Itsukushima Shrine stands the statue of Taira no Kiyomori, erected in March 2014 (Heisei 26). The statue commemorates the 830th anniversary of Kiyomori’s death and is said to face Kyoto. In addition, Rokuharamitsu-ji Temple in Kyoto preserves a seated statue of Taira no Kiyomori, an Important Cultural Property from the Kamakura period.

Summary

The large-scale reconstruction of Itsukushima Shrine undertaken by Taira no Kiyomori in 1168 was more than a chapter in shrine architecture—it marked a turning point in Japan’s politics, economy, and culture. Having secured control of the Seto Inland Sea and amassed vast wealth from Song-dynasty trade, Kiyomori channeled this power into Miyajima’s magnificent floating shrine.

The cultural legacy he fostered—the shinden-zukuri layout, the dedication of the Heike Nōkyō, and the spread of kangen music and bugaku—still animates Itsukushima Shrine over 850 years later. Although the Heike fell, the shrine Kiyomori envisioned has been cherished across the centuries, earning UNESCO World Heritage status in 1996. When you visit Miyajima, pause to imagine Kiyomori’s dream—and the passion that set a sea shrine shimmering upon the tides.

References & Sources

- Cultural Heritage Online: Itsukushima Shrine: Main Hall, Heiden Hall, Haiden Hall

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website: History

- Miyajima Tourism Association: Itsukushima Shrine

- WANDER National Treasures: National Treasures – Paintings | Heike Nōkyō

- Rokuharamitsu-ji Temple: Temple Treasures

- Hiroshima Cultural Encyclopedia: Hiroshima’s Cornerstone “The Heike and Itsukushima Culture”

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, Miyajima Town History: General History Volume, Miyajima Town, 1992

- Fukuyama Toshio, Architecture of Itsukushima Shrine, Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 1988

- Nishi Kazuo, Architectural History of Itsukushima Shrine, Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2005

- Komatsu Shigemi, Research on the Heike Nōkyō, Kodansha, 1996