Itsukushima Shrine was built out over the sea to keep human footsteps off land considered holy across the entire island. Shaped by ancient reverence for Miyajima and Taira no Kiyomori’s vision for a grand maritime shrine, this one-of-a-kind complex has been preserved as an unmatched masterpiece of over-water architecture—and a must-see landmark in Hiroshima for travelers to Japan.

Why Build a Shrine on the Sea? Tracing Its History

Miyajima: Sacred Since Ancient Times—An Entire Island Devoted to the Gods

The reason Itsukushima Shrine stands above the sea is rooted in the deep devotion to Miyajima that has endured since antiquity. The name “Itsukushima” itself means “island devoted to the gods,” reflecting the belief that the whole island was a sanctified realm.

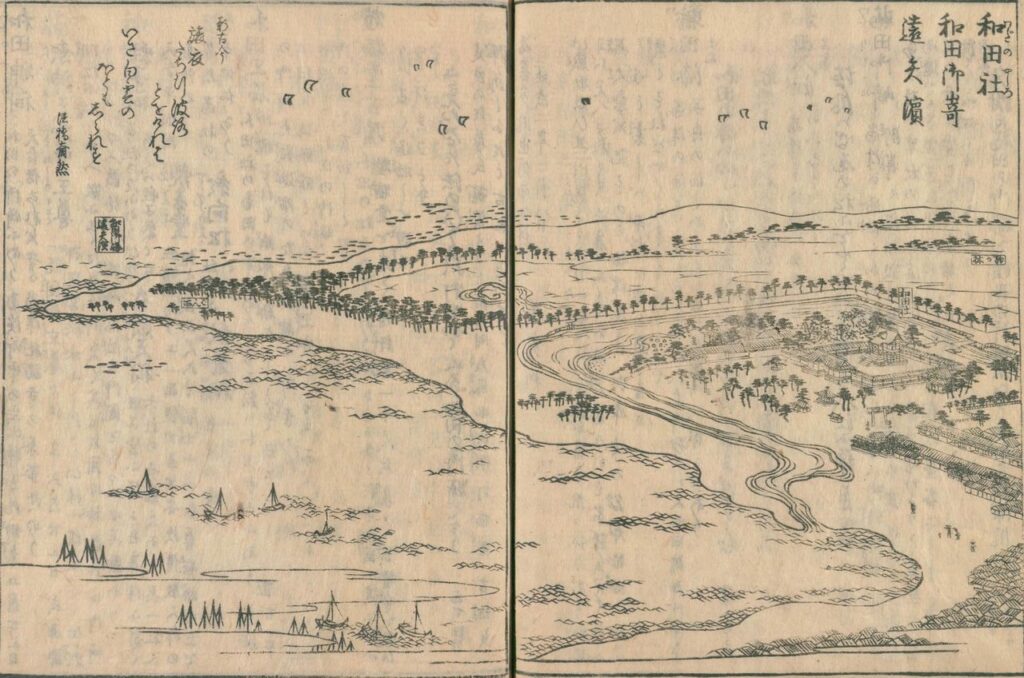

Long before the Heian period, Miyajima was venerated as the dwelling place of deities safeguarding navigation in the Seto Inland Sea. People considered setting foot on this holy ground an awe-inspiring act, which led to the custom of worshiping from boats or from the opposite shore. This profound reverence became the spiritual basis for building a shrine that faced—and floated upon—the sea.

Archaeological research has uncovered distinctive ritual sites on ancient Miyajima, suggesting the entire island functioned as one vast sanctuary. Its geography—an island encircled by water—naturally emphasized its separation from the everyday world and reinforced its character as a divine domain.

The Magnificent Sea Shrine Built by Taira no Kiyomori

The striking “floating” layout of today’s Itsukushima Shrine was magnificently rebuilt by Taira no Kiyomori in 1168 (the 3rd year of the Ninan era) during the late Heian period. Visiting Miyajima as Governor of Aki Province, Kiyomori was moved by the island’s mystical beauty and long-standing faith. He resolved to create a great shrine complex, praying for the prosperity of his clan.

Kiyomori’s plan went beyond shrine construction. It envisioned a maritime hub overlooking the Seto Inland Sea. The Taira clan relied on the protection of the Itsukushima deities—patrons of safe sea travel—to secure control of vital shipping routes. The over-water sanctuary became a symbol of Taira maritime power and a beacon for sailors.

Adapting Kyoto’s elegant shinden-zukuri palace style to a marine setting, Kiyomori created the dreamlike scenery in which the shrine seems to float at high tide. This was a groundbreaking concept in world architecture—an ideal sacred space bridging the realm of the gods with human society. Visitors today can still witness the famous “floating torii gate” rising from the sea, a hallmark image of Miyajima and a highlight for anyone planning a Hiroshima day trip.

Architectural Techniques and Structural Features of the Floating Shrine

Unique Construction Methods Adapted to Tidal Forces

The most remarkable feature of Itsukushima Shrine’s marine design is its engineering to withstand dramatic tidal shifts. The Seto Inland Sea can see a tidal range of roughly 4 meters—conditions that would overwhelm ordinary buildings.

Deep-set camphor wood pillars are driven into the seabed to absorb the pressure of changing tides and waves. Essential to the structure are horizontal “nuki” through-beams that tie the pillars together, allowing the entire building to move as one and resist the sea’s force.

Floorboards are laid with intentional gaps so water can escape when high waves surge in—an ingenious “drainage” strategy that reduces destructive impact. Roof tiles are fastened with special methods to cope with strong coastal winds, enhancing resilience to typhoons and storm surges.

Harmony of the Corridor Architecture and the Maritime Landscape

The shrine’s long corridors are designed to celebrate the unique over-water setting. Stretching about 280 meters and symmetrically arranged around the main hall, they form a striking scene at high tide—like vermilion bridges floating on the sea.

Their height was carefully calculated against tide charts so visitors can walk even during high tide. At low tide, multiple worship routes let you pass beneath or between buildings and approach the grand torii from the shore. This vivid “dual worship experience”—different at high and low tide—is a signature of a shrine built above the sea and a highlight for travelers timing their visit with the tides.

Materials such as camphor, cypress, and cedar were chosen for their resistance to salt air and seawater, with long-term maintenance in mind. Vermilion-lacquered pillars and the green-patinated roof contrast beautifully with the blue sea and sky, creating the otherworldly landscape often compared to a “Dragon Palace” floating on the water.

Cultural Impact and Historical Significance of Maritime Worship

Itsukushima Shrine’s over-water design was revolutionary in Japan’s religious architecture. Whereas most shrines rose on mountains or in sacred forests, this complex created a sanctified space in the dynamic environment of the sea.

Maritime worship also shaped aristocratic culture in the Heian era. Pilgrimages by Kiyomori and the Taira clan evolved into refined cultural occasions featuring court music and poetry recited on the water. The dedication of richly decorated sutras, known as the “Taira Family Sutra Offerings,” highlights the shrine’s unique maritime identity.

From the medieval period onward, Itsukushima’s model inspired shrine-building across Japan, especially for waterside and over-water sanctuaries. Devotion to the Itsukushima deities as protectors of seafarers spread nationwide, leading to numerous branch shrines along the Seto Inland Sea and beyond.

Marine construction techniques were preserved under the protection of the Mori clan in the Warring States period and by the Asano domain in the Edo period. Although the Meiji Restoration’s separation of Shinto and Buddhism affected religious practice, the shrine’s structure and spirit endured. In 1996, Itsukushima Shrine and the surrounding landscape were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing their universal value.

From the perspective of modern architecture and engineering, the shrine’s approach offers enduring lessons: resilience against natural disasters, environmentally sensitive building methods, and a sustainable repair culture refined over centuries.

The Enduring Value of Maritime Architecture in the Modern Era

Today, the value of Itsukushima Shrine’s over-water design is more relevant than ever. In an era of rising seas and stronger storms, the shrine is studied as a model for building in harmony with the ocean.

Particularly notable are its environmental sensitivity and long-term sustainability. The architecture exemplifies “symbiotic design” that avoids damaging marine ecosystems and can even create habitat for fish and seaweed. Centuries of periodic repairs and renewals offer practical insights for sustainable construction and heritage conservation.

The cultural and spiritual rewards are just as significant. As the scenery transforms with the tides, visitors experience how human creativity and natural forces can coexist—an idea modern society often forgets. Welcoming more than 4 million visitors a year, Itsukushima Shrine remains one of Japan’s most iconic sights and a highlight for travelers exploring Miyajima from Hiroshima.

Summary

Itsukushima Shrine was built over the sea because the entire island was revered as sacred, and Taira no Kiyomori transformed that belief into a visionary maritime complex. Engineered to work with the tides, the “floating” shrine stands as a milestone in religious architecture and a cornerstone of Japan travel, from the famed floating torii gate to the elegant corridors above the water.

Born from devotion to a holy island, this maritime masterpiece has endured for nearly a millennium to become a World Heritage landmark shared by all humanity. Its example—coexisting with the sea and embracing natural forces while protecting a beautiful sanctuary—continues to offer timeless wisdom for travelers, architects, and communities around the world.

References and Sources

- Agency for Cultural Affairs, Cultural Heritage Online: Itsukushima Shrine (World Heritage Site)

- Agency for Cultural Affairs, National Cultural Properties Database: Itsukushima Shrine Main Hall, Offering Hall, and Worship Hall

- Miyajima Tourism Association: World Cultural Heritage Registration

- Miyajima Tourism Association: Itsukushima Shrine

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website (National Treasure & World Heritage)

- Hiroshima Cultural Encyclopedia: Foundation of Hiroshima “Heishi and Itsukushima Culture”

- Hatsukaichi City Official Tourism Website “Hatsutabi”: World Heritage “Itsukushima Shrine”

- Wikipedia: Itsukushima Shrine (Japanese)

- Miyajima Town History Compilation Committee, “Miyajima Town History: General History Edition,” Miyajima Town, 1992

- Fukuyama Toshio, “Architecture of Itsukushima Shrine,” Chuokoron-Bijutsu Shuppan, 1988