Gazing up at the vermilion-lacquered torii gate that symbolizes Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima, many travelers naturally wonder: “How can such a gigantic torii stand in the sea without toppling over?” For anyone planning what to see in Miyajima or curious about Japanese shrine architecture, this is one of the island’s most fascinating mysteries.

Surprisingly, the Great Torii is not anchored to the seabed. It stands by its own mass—an astonishing 60 tons. Completed in 1875 (Meiji 8), it embodies time-tested construction techniques that have survived typhoons and earthquakes, showcasing engineering wisdom that still resonates in modern design.

Explaining Why the Great Torii Gate Doesn’t Fall: A Technical Perspective

The Astonishing Weight-Balance Design

The primary reason the Great Torii at Itsukushima Shrine remains upright is its overwhelming weight. Rising about 16.6 meters, the current gate is a massive timber structure weighing roughly 60 tons. That mass is not merely the sum of its wood—it is carefully distributed to keep the structure stable.

The key lies inside the top crossbeams: the shimaki and the kasagi. Unlike typical torii, these beams are box-shaped, and they are packed with stones roughly the size of a human head—about 7 tons in total—that act as counterweights. This lowers the center of gravity and effectively suppresses sway from wind and waves, allowing the “floating” torii to stand firm even at high tide.

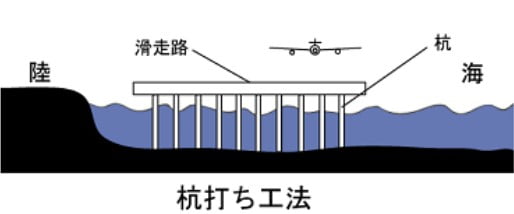

Ground Reinforcement Using the Senbon-kui Pile Method

Supporting a 60-ton gate on soft, sandy seabed requires special ground improvement. Since ancient times, builders have used a technique called the “thousand-pile method” (senbon-kui). Beneath each main and side pillar, 30 to 100 pine piles are densely driven to a depth of around 50 centimeters, spreading the load and stabilizing the base.

Today, a 45-centimeter-thick concrete slab is laid over these pine piles, topped with a 24-centimeter-thick layer of granite paving stones. The Great Torii rests entirely on this robust foundation and is stabilized solely by its own weight. It is not embedded in the ground—it’s essentially “placed” there—yet it remains remarkably stable.

Structural Features and Stability of the Ryobu Torii

A Six-Pillar, Load-Distributing System

The Great Torii at Itsukushima Shrine uses a form known as the Ryobu Torii. It consists of two main pillars, each flanked by two side pillars—six pillars in total. This configuration distributes the load efficiently and greatly increases stability compared with the simpler two-pillar Myojin-style torii seen at most shrines in Japan.

The main and side pillars are integrated using through-bolts at the top and bottom, tightened and secured with wedges. This joinery allows all six pillars to act together, creating strong resistance to lateral forces from wind and waves. Considering that roughly 90% of torii nationwide are Myojin-style, the Ryobu style here clearly prioritizes stability for a marine environment.

The Superior Material Properties of Camphor Wood

The main pillars of the Great Torii are carved from natural camphor wood (kusunoki) trees about 500 years old—exceptional timber prized in Japan. For the current ninth-generation gate, the eastern pillar uses camphor from Miyazaki Prefecture, and the western pillar uses camphor from Kagawa Prefecture. During repairs in 1950, additional root grafts were made using camphor from Fukuoka and Saga Prefectures.

Camphor is chosen for its outstanding properties: relatively high specific gravity, strong resistance to decay, and natural insect resistance. This durability is vital for a structure constantly exposed to seawater in Hiroshima Bay. The vermilion surface coating, called komyotan, is not just beautiful—it also offers practical protection, including anti-corrosion and anti-rot effects that help the wood endure the elements.

Resilience Against Natural Disasters and Historical Performance

The real test for the Great Torii comes during typhoons and earthquakes. Since its reconstruction in 1875, this ninth-generation gate has weathered numerous natural disasters. While Itsukushima Shrine sustained serious damage during Typhoon No. 19 in 1991, the Great Torii endured.

This disaster resilience stems from its sheer mass, low center of gravity, and the seawater environment, which is low in oxygen and slows decay within the submerged sections. That said, marine organisms still cause damage over time—shipworms, wood-boring insects, and encrusting barnacles are persistent foes—so regular maintenance is essential.

During a major restoration from 2019 to 2022—the first in about 70 years—hidden voids 40 to 50 centimeters in diameter and up to 4 meters deep were discovered within the pillars. Damage from termites and decay fungi was repaired with carefully fitted wood infills, seismic reinforcement was added, the cypress bark roof was replaced, and the entire gate was repainted. Thanks to this work, visitors today can appreciate both the beauty and the strength of the iconic “floating” torii in Miyajima.

The Value of Ancient Architectural Techniques Passed Down to the Present

The techniques behind the Great Torii represent the pinnacle of Japanese timber architecture handed down since the Heian period. The thousand-pile foundation method anticipates principles still used for stabilizing soft ground today, while the weight-balance approach echoes the tuned mass and damping ideas used in modern high-rise engineering.

Equally remarkable is the principle of “standing by its own weight.” Modern buildings often assume fixed foundations, which can fail as a single unit in an earthquake. The Great Torii, by contrast, allows controlled play between structure and base, achieving long-term stability through flexibility—an idea deeply rooted in traditional Japanese wooden architecture.

Looking to the future, the Miyajima Millennium Committee continues cultivating camphor trees to ensure suitable timber for future repairs. Their “Forest of Eternity” within Itsukushima’s national forest helps safeguard both cultural heritage and sustainable resource management, ensuring that the Great Torii of Itsukushima Shrine remains a must-see in Miyajima for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t the Great Torii fall over even though it isn’t anchored to the ground?

The Great Torii stands independently thanks to its enormous weight of about 60 tons and a low center of gravity created by roughly 7 tons of stone counterweights inside the upper beams. It also rests on a base reinforced with the thousand-pile (senbon-kui) method, providing ample stability without being embedded in the seabed.

Why is camphor wood used?

Camphor offers ideal properties for marine environments: high specific gravity, strong resistance to decay, and natural insect resistance. This makes it one of the few woods capable of withstanding long-term exposure to seawater around Hiroshima and Miyajima.

What is the Senbon-kui technique?

An ancient ground-reinforcement method for weak seabeds, where 30 to 100 pine piles are densely driven into the sand. A concrete slab and granite paving are then laid above. It can be considered an early form of the pile foundation methods used in modern construction.

Is there any concern it might collapse during typhoons or earthquakes?

The current Great Torii has withstood numerous typhoons and earthquakes over roughly 150 years since 1875. Seismic reinforcement was also added during the 2019–2022 restoration, and ongoing maintenance helps preserve safety.

What is the meaning behind the vermilion color of the Great Torii?

The vermilion paint (komyotan) has anti-corrosion and anti-rot effects in addition to its striking appearance. It exemplifies traditional craftsmanship that blends beauty with durability.

Which generation is the current Great Torii?

Counting from the first gate associated with Taira no Kiyomori, the current one is the ninth generation. It was rebuilt in 1875 (Meiji 8) and most recently underwent major restoration in December 2022—the first such comprehensive work in about 70 years.

Summary

The Great Torii of Itsukushima Shrine remains standing thanks to a design that looks simple but relies on sophisticated engineering. Its approximately 60-ton mass and low center of gravity, the Senbon-kui (thousand-pile) ground reinforcement, the superior durability of camphor wood, and the six-pillar Ryobu configuration all reflect the refined techniques of Japan’s master builders—methods that still inform modern engineering.

Having endured for about 150 years in a harsh marine setting, Miyajima’s “floating” Great Torii represents the pinnacle of traditional Japanese construction and sustainable craftsmanship. When you visit Miyajima, take a moment to enjoy not only its beautiful silhouette at high tide but also the ingenious construction techniques that keep this iconic Hiroshima landmark standing tall.

References and Sources

- Miyajima Tourism Association: The Great Torii Gate

- Itsukushima Shrine Official Website: Construction Status and Plans

- Masuoka Corporation: Itsukushima Shrine Great Torii Major Restoration Project

- Hiroshima Tourism Association – Dive! Hiroshima: Miyajima Itsukushima Shrine Great Torii Renovation Completed

- Wikipedia: Itsukushima Shrine Great Torii (Japanese)

- Japan’s World Heritage: Itsukushima Shrine

- Hatsukaichi Own Media: Is the Torii Gate of Itsukushima Shrine Floating?